The 4th Medical Battalion, a unit of the U.S. Marine Corps made up of Marines and U.S. Navy personnel, wanted to up the training and preparation of medical and surgical teams that support Marines in the field. Specifically, it wanted to know how it could “more effectively resource, organize, and provide medical training that realistically reflect the austere environments and patient conditions, while optimizing for the availability of critical training equipment.” Marines’ health and safety are quite literally on the line.

Thanks to the National Security Innovation Network and a Development Engineering class at Berkeley, the battalion found a potential answer: Vytals.

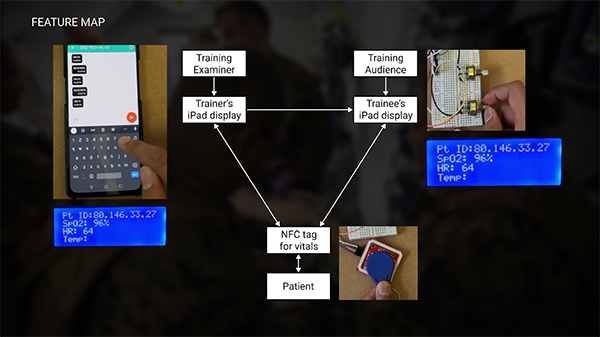

The student team in last spring semester’s DevEng 290: Innovation in Disaster Response, Recovery, and Resilience (IDR3) — Abhi Ghavalkar (Master of Design), Michelle Williams (Interdisciplinary Studies), Pranav Vanjani (Master of Engineering – Product Design), Sudeshna Naik (Master of Development Engineering), and Vishal Ramesh (Master of Engineering – Product Design) — developed a near-field communications patient-management tool for training medical teams in the field and tracking patients’ vitals in real-time without an internet connection.

The team, which named their final prototype Vytals, was paired with the U.S. Marine Corps’ 4th Medical Battalion early in the class.

“This was a great learning experience,” Naik said, “and I learned how to maximize my critical thinking abilities, managerial skills, conduct research, and develop prototypes.” She said she valued the “opportunity to visit the training site and conduct in-person interviews with the 4th Medical Battalion’s surgeons and corpsmen.”

IDR3 started out as just IDR: “Innovation in Disaster Response.” It was the brainchild of Vivek Rao, a lecturer at Haas School of Business and a researcher in mechanical engineering, and Rachel Dzombak, a former lecturer and researcher at Berkeley and now a full-time researcher and adjunct faculty at Carnegie Mellon University who played a key role in developing DevEng curriculum. They wanted to explore the skill sets needed to solve messy complex problems, including in humanitarian assistance and disaster response: framing and solving those complex problems, experimenting with emerging technology, taking a systems mindset and approach to solving problems, and working in interdisciplinary teams. Key is taking a human-centered approach, understanding the real people who are experiencing the problem and who have a stake in it, and thinking through the role technology can play in a solution that fits the problem, and not vice-versa.

IDR became IDR3, and students were connected to national-security agencies by the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN), a program office under the U.S. undersecretary of defense for research and engineering that connects new communities of innovators, academia, and early-stage ventures to solve national-security problems. Though it’s a DevEng course, students come from a wide array of disciplines. The class is gender-balanced and includes undergrads. Vytals was one of five teams in the 2022 iteration.

“The course intends to draw on the domain expertise of project sponsors, the critical thinking and innovation skills of students, and the frameworks that we as instructors provide,” Rao said. “Of these, Berkeley students shine the most: Working with sponsors presents students with a set of challenges unique from other courses, and I’ll be the first to say that we instructors are constantly learning and are far from perfect.

“Berkeley students drive the story in this class,” he added. “They are so passionate about making tangible differences in the world that they negotiate project and class challenges with alacrity and grace, something that’s true for the range of talent that elects to join the class, whether from engineering, architecture, public policy, or another discipline entirely. The Vytals team absolutely embodies that.”

The team also benefited from a travel award provided by NSIN partner Common Mission Project, a nonprofit platform for creating mission-driven entrepreneurs who can tackle pressing problems in everything from natural disasters to national security. CMP and IDR3 shared a philosophy of what CMP director of strategic partnerships, Tyrome Smith, called “beneficiary discovery.”

“Unless and until you really get to know your customers, you’re really just guessing,” Smith said of innovators seeking to help a specific community. “Sometimes you actually have to see them in their natural environment. You can’t talk to Marines who are trying to develop a sense of triage in the medical environment, for example, and ask, ‘How do you do triage in your medical environment?’ Nope. You’ve got to go visit.”

For CMP, fundees didn’t need to have working prototypes or business plans in place, but that “they’re going there with purpose” — to see, in this case, what the 4th Medical Battalion did, in order for Vytals to evaluate and revise their own hypothesis to best address the battalion’s problems.

So during the spring, part of the Vytals team visited the battalion at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar East in San Diego to check out fast-paced field exercises in an intensive, desert-like environment. They found that suboptimal organization and lack of space meant lost time when simulating medical scenarios, that Battalion members had difficulty identifying needed supplies during these simulated time crunches, and that they had a hard time tracking patient information and vitals.

“Doctors in the field are required to sift through [authorized medical allowance list] boxes for four to six hours every time in order to organize the medical supplies for easy access,” Cdr. Chrystine Lee explained to the team. Capt. Alan Flanigan told them: “We literally write a patient’s vitals on a sticky note and stick it on the patient’s forehead to keep track of their medical status.”

“This was our first foray into working with an educational institution to develop the ideas behind a military solution,” LtCol Sarah Pezzat, the battalion inspector-instructor, said. “Each student attacked the problem from their own unique perspective and honestly thought of potential solutions and took this project in new directions that I’m not sure we would have done on our own.”

Visiting the Marine Corps installation, LtCol Pezzat added, “helped give them a much more nuanced and detailed understanding of our operational and training challenges.”

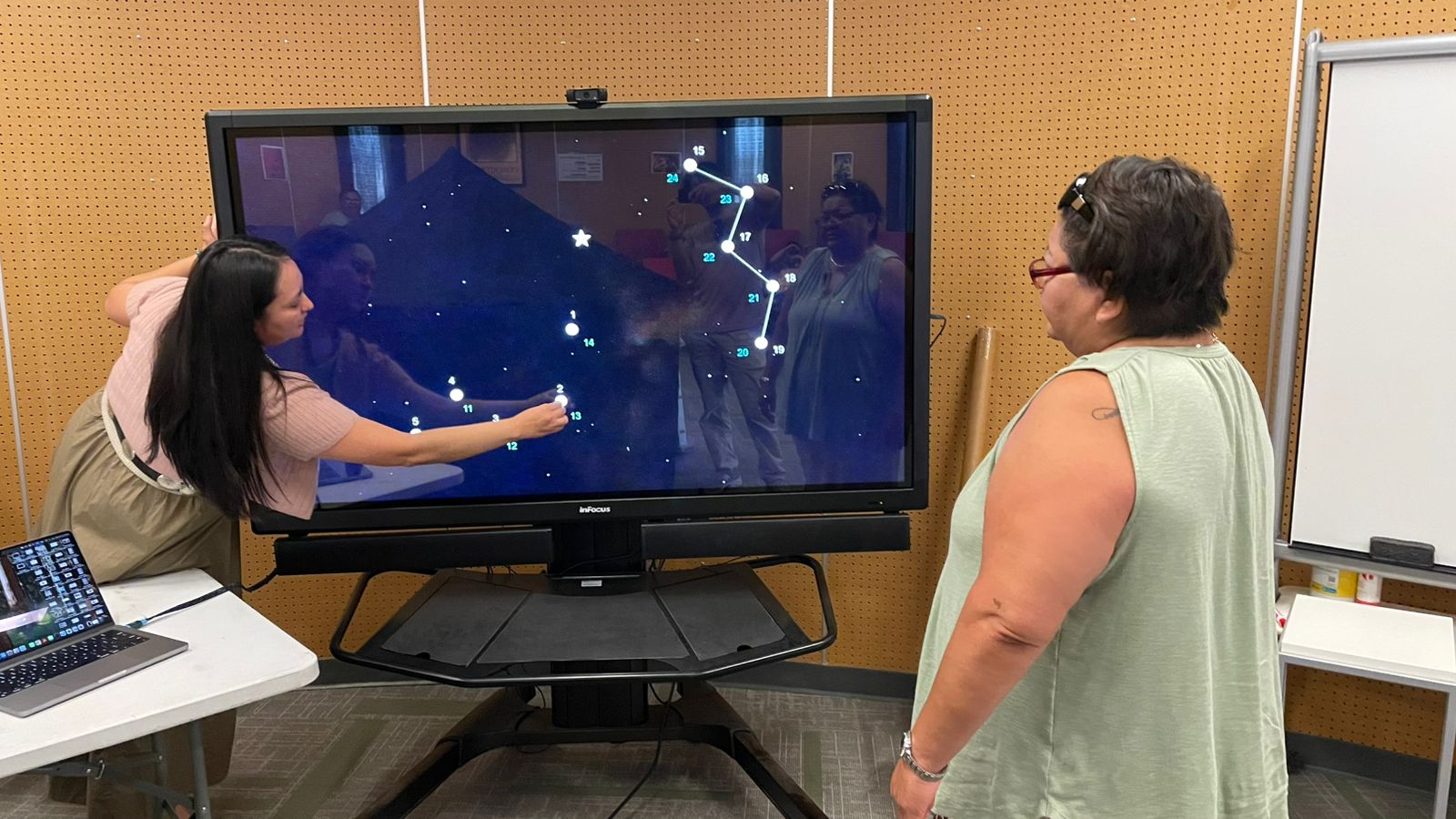

From those in-the-field observations and numerous interviews with battalion members, the team reframed the problem to focus on providing a “realistic representation of field scenarios while optimizing preparation, organization, and utilization of medical equipment,” and got to work on three prototypes. The third was the battalion’s preferred solution: offline-capable patient tracking. Near-field communications (NFC) tags on patients’ skin monitor their vitals and relay them to caregivers’ devices without the need for internet. Caregivers can monitor their patients’ statuses in real time. A digital interface for trainers allows them to simulate realistic medical scenarios with trainees, who can respond in the system with how they should address the “patient.”

The team’s greatest challenge, Naik said, was “trying to nail down one problem statement that is both within the project’s scope and also meets the needs of all stakeholders.”

“The most rewarding aspect,” she noted, “is to see how this project will make a real difference to the training process and prepare the 4th Medical Battalion for deployment.”

Though the class is over, Vytals’ run isn’t. Naik has adopted it as her M.DevEng capstone project, and the 4th Medical Battalion is keen on seeing it reach the testing phase and then on to production.

“Developing two of the ideas the Berkeley team came up with would not just benefit the 4th Medical Battalion,” LtCol Pezzat said, “but likely the military medical community as a whole.”