After attending a conference on electric lighting efficiency in New Delhi, India in 1995, Dr. Evan Mills stopped by Varanasi for a vacation.

One night, he wandered through a car-free warren of alleys lined with shopkeepers. Standing against a wall in the marketplace watching humanity flow by, he had an epiphany — one that

would help pave the way for the adoption of off-grid solar lighting on a wide scale.

“I look down to my left, and there’s a man with a blanket spread out, three feet by three feet. He’s selling bracelets and beads, and he’s got a kerosene lamp that’s lighting his wares, and everything’s sparkling,” Mills, then a scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, recalled. “And that was the proverbial ah-ha moment.”

At first glance, such lamps have an enchanting aura to them. But after that conference, Mills couldn’t help but wonder how much fuel the vendor was using, how much carbon dioxide was being released, how many others out there relied on this dim source of light to practice their business, and whether viable alternatives could be developed and brought to market.

“And then I started this odyssey,” he said, “that went on for decades to really try to nail that down.”

With support from the Blum Center and several other funders, Mills and his colleagues addressed a gaping hole in lighting research. They provided the first substantive analysis of how electric lighting — specifically, high-efficiency solar-powered electric light sources unattached to an electrical grid — improves the lives and wellbeing of people using fuel-based lighting. He calls it “wireless lighting.” They went on to create and implement international standards for such products.

GOGLA, an international organization that later picked up the mantle of this work, has reached about 140 million people in the developing world by supporting dozens of companies and investors. Non-profit groups such as Light Up the World also did pioneering work on this problem.

Fuel-based lighting, on the other hand, like the Varanasi merchant’s kerosene lamp, is associated with various health, environmental, and economic problems.

Beyond the difficulty in doing basic activities under such dim and inefficient light sources, they are fire and burn hazards and can wreck indoor air quality. They are orders of magnitude more expensive than fluorescent or even “inefficient” incandescent lighting, per lumen (a unit of brightness).

“A homeowner [in the U.S.] spends maybe five percent of their income on energy,” including for their car, house, heating, cooling, refrigeration and more, Mills explained. “A very poor person can spend five percent of their income on kerosene lighting alone.”

Under the Lumina Project, Mills organized his studies of off-grid lighting solutions for low-income communities around the world, as well as the provision of information and analysis to consumers, industry, and policymakers.

Mills’ mentor, Arthur Rosenfeld, won the Department of Energy’s 2005 Enrico Fermi Presidential Award and a $375,000 honorarium.

“He just gifted it to the Blum Center and said, ‘Here, do something good with it,’” Mills said.

That good funded the Lumina Project and other activities at the Blum Center.

“We were very lean and mean,” Mills said, applying the Center’s funding to equipment purchases, travel to countries for research, and supporting Berkeley students getting involved in the project. “We made the resources go really far.”

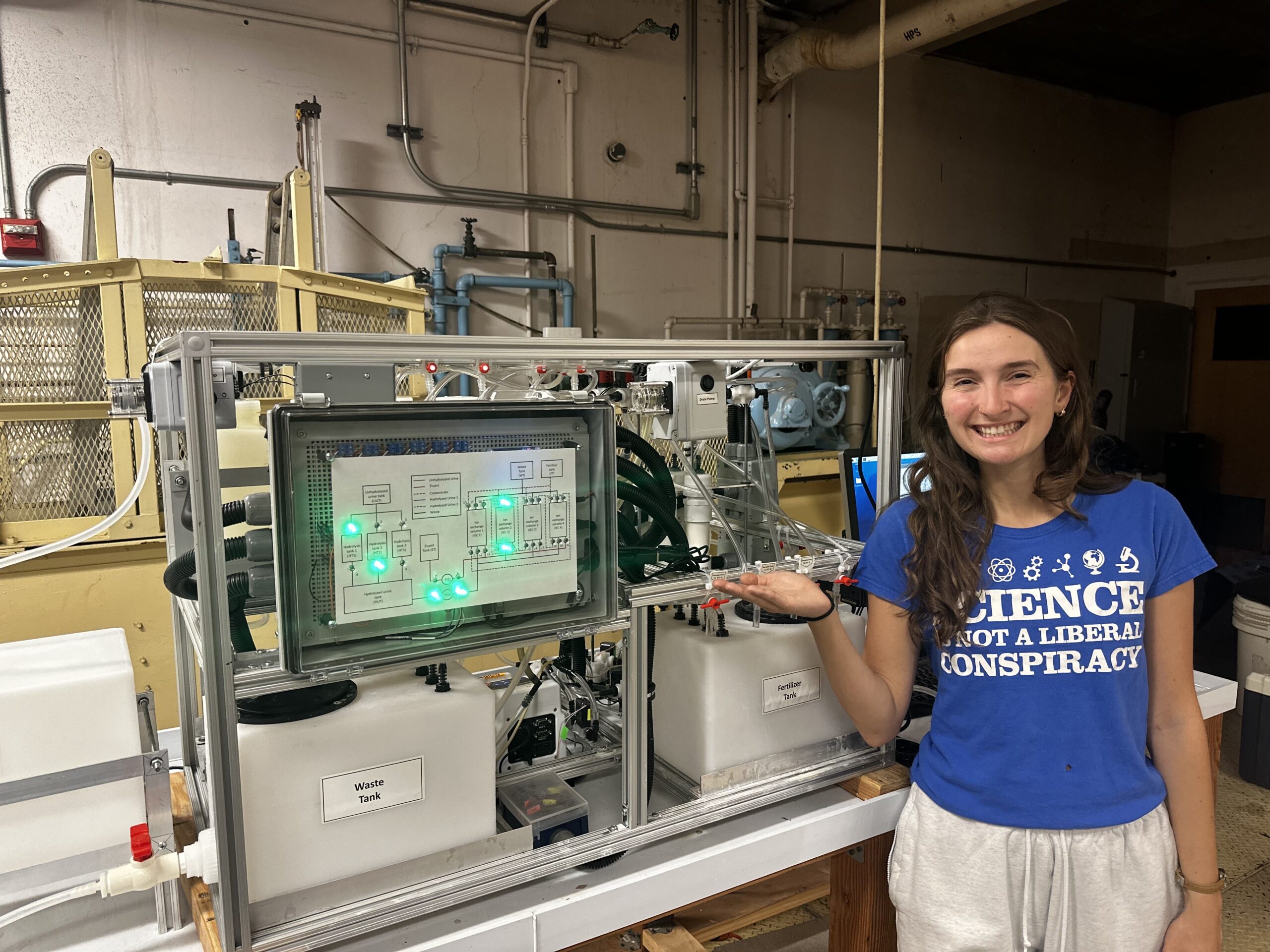

A huge area of research Mills and his team were able to pursue was market characterization and needs assessments. On the technology side, white LED lights had just been commercialized, which meant that by packaging small rechargeable lithium or nickel-cadmium batteries and tiny solar panels, one could create portable and affordable solar lanterns at a fraction of the cost of bulky incumbent systems. Miniaturization and pre-purchase assembly of components stood to be major breakthroughs.

Users of fuel-based lighting are “not a monolith,” Mills said. “It’s not just a kid with a lantern doing their homework.” It’s also a doctor treating patients in a clinic, a schoolteacher in a windowless classroom trying to light their chalkboard, fisherpeople on a lake at night, chicken growers, nighttime security guards, people in cottage industries, and women moving around refugee camps. How did all these people use light? What did they pay for it? What were their nuts-and-bolts engineering needs?

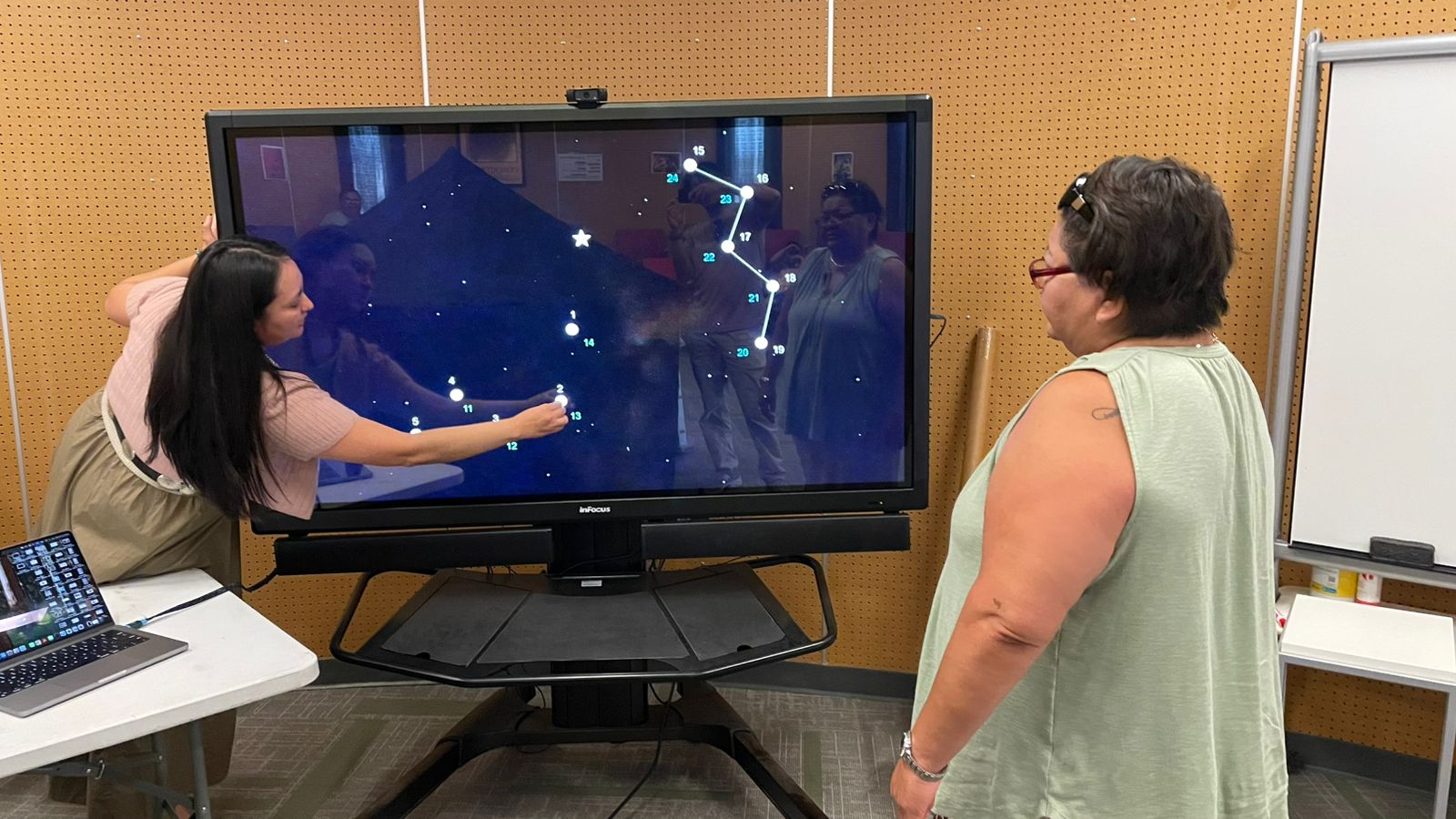

From Kenya to India, Tanzania to Bhutan, Mills and his Berkeley students would take prototypes of portable electric lighting sources — which don’t require special expertise to set up — into communities and be peppered with questions by prospective users already well versed in issues around lumens and durability.

When a community’s health clinics adopted off-grid solar lighting, postnatal maternal mortality decreased, as did infection rates. At kerosene-lit night markets, the diverse colors of goods like flip-flop sandals would wash out into the same hue; under LED headlamps, the colors became immediately distinguishable — along with enough light for vendors to count change under the table. Unlike candles and lanterns, solar lanterns would keep working in the wind and rain, and users weren’t vulnerable to fuel shortages or price spikes.

The funding from the Blum Center also allowed students to spend weeks in Kenya and Tanzania to join night fishing trips on Lake Victoria.

Some 100,000 people go out onto its waters each night, Mills said, with kerosene lanterns floating on little rafts to attract the fish’s food sources, which allows fishers to draw the fish into their nets. But half their income from one night’s catch would go toward kerosene for the next night’s trip, keeping the people impoverished.

Mills and his team built prototypes of LED lamps, and the students spent night after night weighing fish caught with the kerosene and electric lamps and comparing the costs associated with both kinds of catches. The electric lamps essentially doubled their income. They got the same results on Lake Tanganyika and at sea.

They also dug deeper into the health effects of fuel-based lighting: not just the worse indoor air quality and the deadly fires that kerosene lanterns can cause, but synthesizing the literature from doctors treating young children who had been burned by these lamps or had accidentally consumed kerosene. They learned that people who suffered medical emergencies at night often had to wait until daylight to be seen at a clinic, exacerbating their illness or injury and causing longer clinic lines for everyone.

Mills also shed new light on the scale and effects of kerosene subsidies ($35 billion annually), the potential for job creation with electric lighting, and the resources the latter required. They estimated that 150,000 jobs in the world involved kerosene lighting, but the widespread adoption of off-grid solar lighting could potentially produce two million jobs. They also figured out the energy and resources it took to make their LED lanterns and how long those lanterns would have to be used to make up for what was put in. (Twenty to fifty days for a device that would last years.)

There was, however, one snake in the garden. More and more companies were producing affordable, turnkey off-grid solar lighting devices. Mills’ team tested many of them and found considerable variability in the quality of their light output, batteries, wiring, and more.

“Eventually the World Bank got a whiff of this,” Mills said — specifically its International Finance Corporation. Mills helped them develop a successful proposal to the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) to scale up a market-transformation effort.

Mills brought aboard Arne Jacobson of Cal Poly Humboldt’s Schatz Energy Research Center, who, while a PhD student in Cal’s Energy and Resources Group, had studied why older solar lighting systems — featuring big panels, long fluorescent tubes, and heavy car batteries that required an electrician and a year of income to buy — hadn’t been widely adopted. Virtually every obstacle could be overcome with the emerging compact LED systems.

Building on that work, the Berkeley Lab–Humboldt collaboration helped IFC develop test procedures and create a quality-assurance program. At the core was a product-certification program (today called VeraSol). Companies took to it quickly, Mills said, learning how to improve their products. And a warranty and truth-in-advertising component was essential to prevent market spoiling: users having a bad experience with a deficient product and giving up altogether on off-grid electrical lighting.

The momentum for off-grid lighting kept building. A regular conference, organized by IFC, attracted people from dozens of countries, including environmentalists, government officials, and investors. A vibrant, online social network was set up where folks around the world shared insights and innovations, troubleshooted issues together, and found community. As a sign of the gradual mainstreaming, television soap operas in Africa depicted people purchasing solar lanterns.

Eventually the United Nations took note.

The UN Environment Programme wanted to know the carbon-offset value of using a solar lantern, and commissioned Mills and his colleagues to develop a methodology the UNEP could use to evaluate the use of solar lanterns in carbon markets. Their methodology’s adoption came at a critical time given what had been learned about the variability in product performance and quality.

Despite all the success, Mills said, the World Bank and IFC did not intend to stick with off-grid lighting indefinitely, and the movement needed a new organization to continue carrying the torch.

Its proponents founded the Global Off-Grid Lighting Association, which shortened its name to GOGLA once it expanded to include compact and portable solar home kits that made solar energy services more affordable and useful beyond just lighting. GOGLA now assists the off-grid solar community with finance, consumer protection and standards, market insights, advocacy, policy, and more.

Mills, now retired from Berkeley Lab, has moved on to work on other problems. When he started this work, over a billion people lacked electricity. Some 140 million people across the developing world now benefit from the improved products, with about 7 million solar lanterns and multi-light kits and 1.6 million full solar home systems sold each year.

Berkeley students were essential to collecting the data that became the backbone of what the off-grid industry has become, Mills said. As was the Blum Center’s flexibility.

“Complex undertakings like this do take time, and they take patience and dedicated sponsors,” he said. “The Blum Center generously provided us with a lot of trust and latitude to be nimble and respond to new ideas and opportunities.”

“It was so exciting because it was such a green-field area,” Mills added. “There were other people who were poking at this, for sure. But we were right there at the beginning, and the Blum Center was right there on the ground floor with us.”