This past summer, UC Berkeley School of Education Ph.D. student Jessica Benally returned to the high deserts of her youth in New Mexico, just an hour away from her childhood home in Tohatchi in the Navajo Nation.

As one of six UC Berkeley students invited to take part in a new groundbreaking partnership program at Navajo Technical University (NTU), she set out to bring Navajo (Diné) culture into the classroom.

By combining Diné astronomy with mathematics, her doctoral project offers students a new way to learn math: looking up at the stars.

“In some math textbooks, students used the image of a ferris wheel that’s half above ground and half below ground (to understand angles),” Benally said. “But a ferris wheel, half above the ground, is not something students really see, so how about using an example of something that they can actually see?”

For her, the answer lies in the skies, where the rotations of Diné constellations like Náhookos Bi’ka’ (Ursa Major) and Náhookos Bi’áád (Cassiopia) seasonally rotate around Náhookos Biko’ (Polaris) reflect the 90-degree increments of the unit circle.

This type of visualization, she said, made math more accessible in her own childhood, and the insight inspired her to start work on STARR, or the Students Tracking Angular Rotation Recorder — a learning tool for teaching students about angles using their bodies and Diné star knowledge.

Beyond studying shapes on a piece of paper, students move their arms and bodies to create and measure angles while “traveling” across constellations in a small planetarium.

Over the summer, she would get the opportunity to further develop the model in New Mexico as part of her internship at NTU, offered through the collaboration between UC Berkeley’s Development Engineering (DevEng) programs and NTU’s Electrical Engineering (EE) program.

The six students part of the summer partnership program — including Benally and five others from the MDevEng program — were invited to NTU’s campus to work with faculty and fellow students on a variety of engineering projects, ranging from solar energy to air quality monitoring.

“In DevEng, we think a lot about under-resourced communities globally, but there are a lot of communities within the U.S. that are also marginalized,” UC Berkeley DevEng Director Dr. Yael Perez said.

“Being able to work with these communities, who are rich in culture but have limited access to other resources, and be part of their daily life for a short period of time, was a powerful experience, especially for students who come from other rich cultures who experienced marginalization elsewhere.”

The partnership took shape back in 2022, when Perez and NTU professor Peter Romine presented the idea of a joint engineering curriculum for Native American students at the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) conference in Minneapolis.

Perez, who also serves as the program coordinator for the Native FEWS Alliance — a cross-institutional initiative to expand participation in Food, Energy, and Water Systems (FEWS) education to all students, including Native Americans — helped put their vision into action.

Initiated by the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC), the Alliance’s “backbone,” the collaboration opened doors for Berkeley students to intern at NTU, teaming up with faculty and peers on engineering projects in a month-long program in Crownpoint, New Mexico.

Students in the program stayed in the NTU dorms, and spent their time outside of engineering exploring the Navajo Nation and learning more about the culture from school staff, according to Kathy Isaacson, Native FEWS Program Coordinator at AIHEC.

“The six students from Berkeley really hit the ground running when they arrived at Navajo Tech,” Isaacson added.

For Benally, the partnership provided a chance to further her work on STARR within the community she aims to serve.

The project’s main goal is to combine different epistemologies, a term referring to “ways of knowing” or the different frameworks we use to understand the world around us. Benally’s curriculum weaves together Diné and western epistemologies, encouraging students to approach mathematics “pluralistically” through cultural storytelling and scientific methods.

The model pairs two students together: one serves as the Sensor, using an arm protractor to “become” each star in a constellation, with their arms forming the rays of an angle. The other acts as the Navigator, using a digital compass to guide the Sensor to the correct star position.

Together, they trace constellations such as the Navajo Big Dipper (Náhookos Bi’ka’), combining cosmology and computation to make math education more engaging.

Traditionally, the Diné people have looked to constellations to track seasonal changes that guide farming, ceremonies, and other aspects of life, while also using them to build cultural philosophies and traditions. Building on this legacy, STARR blends both — along with other mathematical concepts — to help students grasp angles.

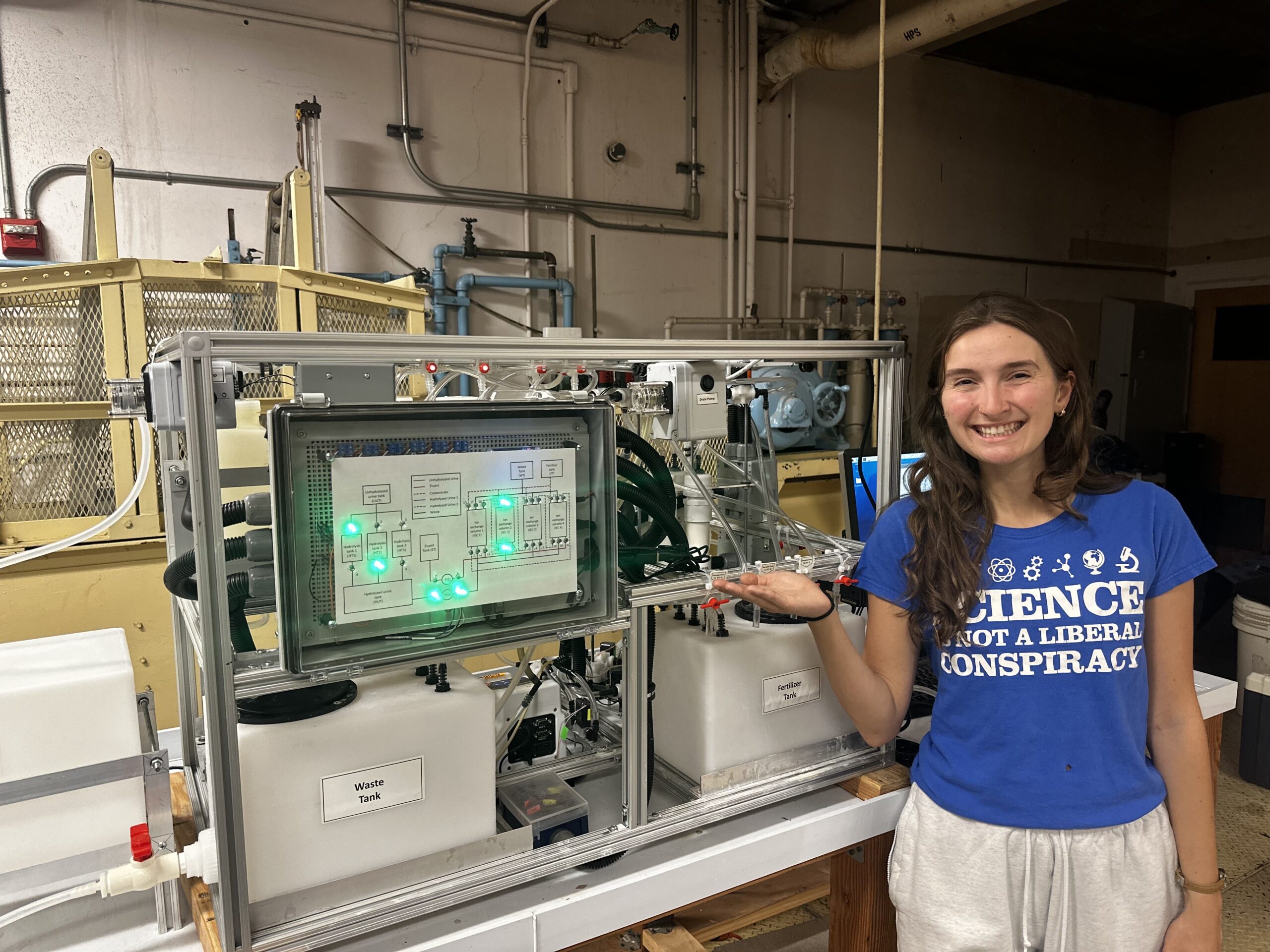

Originally, Benally improvised her tools, using a standard arm protractor made with tape and plastic tubing. Through her internship at NTU, she was able to refine the design, learning how to 3D-print protractors and develop more user-friendly compass tools based on participant feedback.

Benally also worked with former NTU student Hansen Tapaha to create “outreach kits” for K–12 students, designed to spark interest in engineering and incorporate technologies used in STARR.

As part of her ongoing work on the project, Benally was able to host two demonstrations of STARR at NTU for local students and staff through the collaboration. She plans to continue collecting data for the project, with the goal of presenting a final product as part of her dissertation.

“It was really amazing to get guidance from faculty expertise,” she said. “Being able to see it put together was really beneficial to making design improvements that will help the participant experience.”

At its core, each internship offered Berkeley students the chance to learn alongside the communities and traditions their work aimed to support, a hallmark of the DevEng mission, which trains students to tackle the needs of underserved populations.

The DevEng programs, which include both a master’s diploma and a doctoral emphasis, combine advanced technology training with human development studies, preparing students for technical problem-solving and cross-cultural collaboration on the world’s most pressing humanitarian issues.

Perez emphasized that the NTU partnership allowed students to put these lessons into practice by listening to and working directly with underrepresented groups like the Navajo Nation.

“Institutions like NTU and other tribal and community colleges are deeply embedded within their communities, which makes them vital partners in any effort toward meaningful, place-based impact,” Perez said. “This really makes DevEng–NTU an exciting addition to the Native FEWS Alliance.”

Many students who participated in the program are still working on parts of their project, which may turn into capstones they can continue developing at Berkeley in the fall semester.

Following this summer’s success, Perez said that they plan to expand the partnership by bringing NTU students to Berkeley and potentially hosting a joint course between the two schools.

She added that they are also looking to extend the invitation to other universities as well.

“Native American communities are very rich in culture and history, and they know what they want to incorporate in their current lifestyles,” Perez said. “It was really great to be part of that conversation.”

For Benally, the summer at NTU was an unexpected homecoming — a return to the high desert where her love for learning began, now enriched by the knowledge and perspectives she gained at UC Berkeley.