World Water Week is an annual conference and global observance focused on addressing the world’s most pressing water-related challenges — calling on policymakers and innovators to take action on sustainable water solutions.

This year’s theme is “Water for Climate Action,” which aims to address the crucial role that water plays in global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the effects of climate change.

To understand how water-infrastructure innovations can combat poverty and address a changing climate, we spoke with Prof. Kara Nelson, a water infrastructure expert who also serves as the chair of the Development Engineering programs.

What water-related DevEng projects are you working on right now?

One of the biggest threats to clean drinking water in the world is the unsafe management of human waste, because a majority of the planet still doesn’t have access to safe ways of disposing of their fecal waste.

We’re trying to work at one of the root causes of the problem, so we’re working on strategies to collect, contain, and process human waste to then actually create value with it.

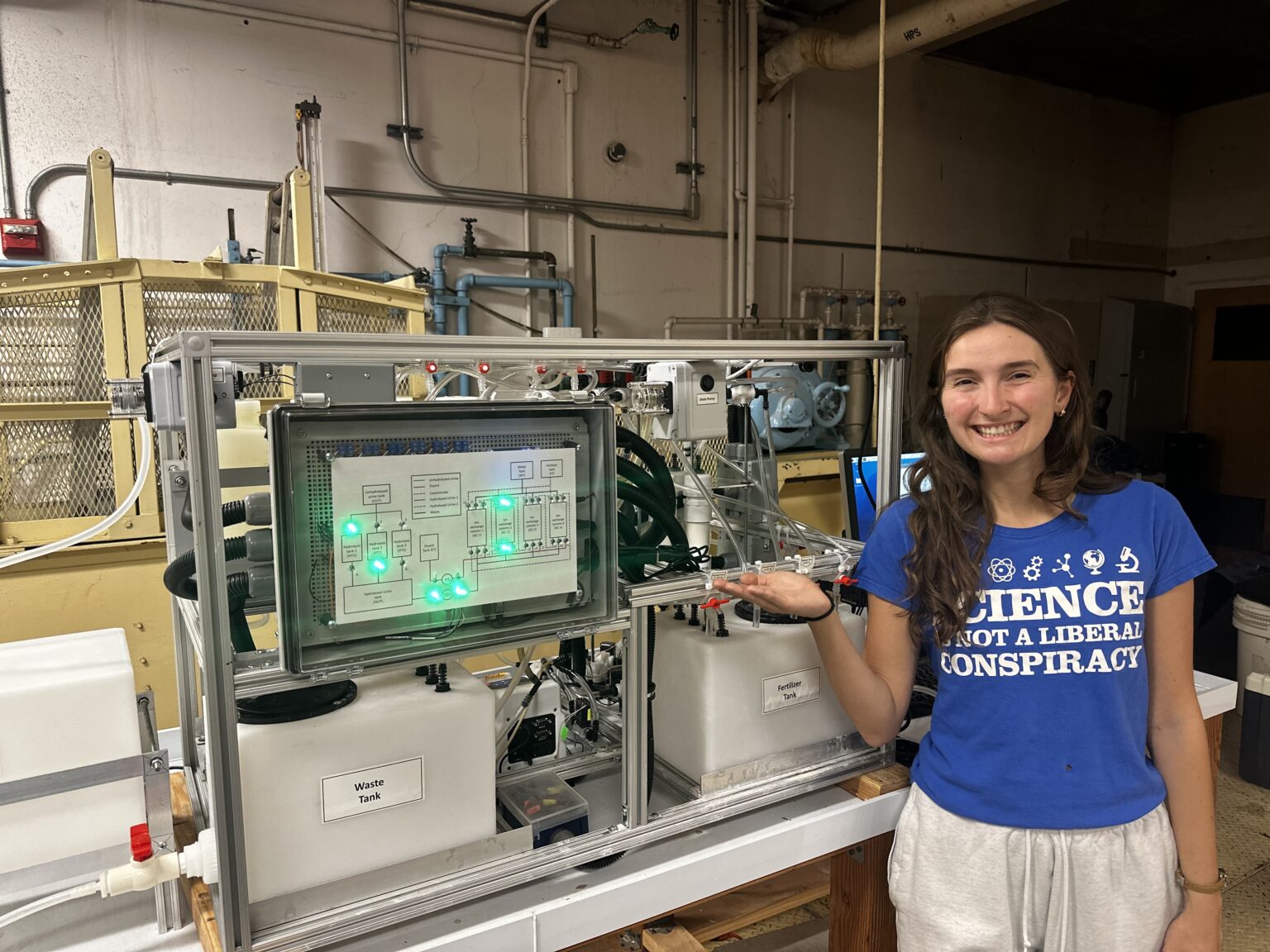

One of the ways we can do that is through a really cool toilet design which separates urine and feces. We can then take the urine and make fertilizer from it.

In a lot of regions of the world, fertilizer is also in limited supply — either because of a lack of availability or because it’s not affordable — so through this project, we can create a local fertilizer product that farmers can use to increase crop productivity.

The main place that we’ve been working to understand the practical aspects and feasibility of this approach is in Kenya.

Why do so many parts of the world still struggle to access safe drinking water?

We think that this approach to capturing urine and producing fertilizer from it can make sense in high income, as well as middle and low income contexts around the world.

What communities would this project be serving?

There are easily a billion people in the world that this solution could work for, but it would very much need to be adapted to the local context.

For example, we’ve been designing the full solution for a context like San Francisco, where people rely on flush toilets. We’re thinking about the technology needed for making the fertilizer that would be designed for spaces like the basement of an apartment building in the Bay Area.

So this is a solution that I think can be appropriate for any community in the world, but things like the user interface are going to be designed specifically for the local context.

This year’s theme for World Water Week is “Water for Climate Action.” How does your project aim to combat climate change?

This sanitation research has many ties to climate change, and it’s trying to address different dimensions of the climate crisis.

One of those dimensions is that if we could produce fertilizer locally from human waste, it would mean that farmers could use less synthetic fertilizer, and synthetic fertilizer is one of the most carbon-intensive products in the world.

All of the fertilizer that’s currently made makes up about two percent of the carbon footprint in the world, so if we could eliminate the production of that synthetic fertilizer, it would reduce global carbon emissions by two percent, which is huge.

Another dimension is that in communities across the world without access to flush toilets, developing waterless solutions — through nonflush adaptations of our solution — that are acceptable to users offers a great way to address growing water scarcity.

Because of climate change, more and more of the world’s population is going to live in regions with severe water scarcity, and one of the most water-consuming activities in the United States is flushing toilets.

We take water that’s of drinkable quality, and we flush it down the toilet. If we can develop solutions for sanitation that use no water or use less water, that is going to help us adapt to a dryer and warmer climate.

As DevEng chair, what role do you see Development Engineers playing in the push for climate action?

We always need to be thinking of ways in which any type of water infrastructure contributes to the climate crisis. We need to be asking ourselves how we can reduce those impacts, and then, how we can also develop infrastructure that is adapting to a changing climate.

Water solutions for conditions we have today may not be adequate 10, 20, or 50 years from now, so we need to be planning for the inevitable.

Even if all of us were able to eliminate carbon emissions today, there’s enough momentum from all the historical greenhouse gas emissions that the climate is going to change, and the most marginalized are going to experience the greatest impacts from climate change.

So, we really need to be prioritizing solutions for vulnerable communities around the world, and that’s part of the framing for our Development Engineering programs and curriculum.