In the Fall of 2019, Abby Yue Gao’s first semester in UC Berkeley’s Master of Architecture program, her classes had to repeatedly pause due to another severe California wildfire season. Berkeley was spared the flames, but still suffered power shut offs and dreadful air quality thanks to that year’s worst blaze, Sonoma County’s Kincade Fire. Tens of thousands had to flee their homes; hundreds of thousands faced blackouts. A quarter of the county’s population speaks a language other than English at home — a major hurdle during disasters, when critical information from first responders goes out primarily in English.

The following spring, Gao enrolled in a Development Engineering course, “Innovation in Disaster Response,” taught by Vivek Rao, a lecturer at Haas School of Business and a researcher in mechanical engineering, and Rachel Dzombak, a former lecturer and researcher at Berkeley and now a full-time researcher and adjunct faculty at Carnegie Mellon University. Gao was interested in designing a digital product to solve a real-world problem, and the class pushed students to think about the best way to use technology in a disaster situation.

After research, stakeholder interviews, prototyping, and more, Gao and her teammates, including then–Master of Landscape Architecture student Virginia Wong, created EvacMap, a prototype app for getting out up-to-date evacuation information during wildfires. A little over a year later, EvacMap became WEmap, a research project examining language-based needs in the dissemination of wildfire emergency information. It’s informing the way some of Marin County’s residents with limited English proficiency receive emergency information and resources.

“Sometimes when they receive the alerts or search for information about an emergency,” Gao said, “they might face different problems than native-English speakers.”

“They had very strong user insights,” said Urvashi Agrawal, head of experience for Genasys, the parent company of Zonehaven, a platform that facilitates communication between first responders and communities during emergencies. It’s also the platform on which WEmap prototyped its ideas. Agrawal said Zonehaven is now looking at how the WEmap team’s recommendations and other ideas spawned by them can be incorporated into the platform.

Developing ‘social–technical fluency’

“Innovation in Disaster Response” grew out of Dzombak and Rao’s interest in the skill sets needed to solve messy complex problems, including in humanitarian assistance and disaster response: framing and solving those complex problems, experimenting with emerging technology, taking a systems mindset and approach to solving problems, and working in interdisciplinary teams. It was a Development Engineering class, and only half the students came from engineering and computer science. The class was gender-balanced and welcomed undergrads.

A key aspect of the class — and of all DevEng curriculum, said Dzombak — is “giving students agency so they feel like they can step into these hard problem spaces and make a difference.” That means taking a community-centered approach and understanding who’s already living and working in a community or problem space.

“How do I find leverage points?” asked Dzombak. “How do I start to drive change at those leverage points in a way that is culturally appropriate, that aligns with the humans who are embedded in the system, that acknowledges the power dynamics of the system? And also, what role can technology play to change circumstances?”

One can’t just be a hard-core technologist, but have what she and Rao call social–technical fluency. Students went deep in unpacking disaster-related problems in order to build the right solution — not build a solution in hopes of finding the right problem.

“Innovation in Disaster Response” has since grown into “Innovation in Disaster Response, Recovery and Resilience” (IDR3), thanks to the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN), a program office under the U.S. undersecretary of defense for research and engineering that connects new communities of innovators, academia, and early-stage ventures together to solve national security problems. Now, student groups team up with Department of Defense partners involved in, well, DR3.

“Not only are you giving students a real-world problem for which they can make a tangible difference, but you’re also showing real-world entities and government entities that they can come to an academic institution like Berkeley and find plausible solutions to issues they’re facing,” said Kaitie Penry, NSIN’s program director at Berkeley, which is housed at the Blum Center.

Gao and Wong “were really passionate but not sure of their place in an engineering class,” recalled Dzombak, who was a key developer of UC Berkeley’s Development Engineering curriculum and who still teaches virtually at Haas’ Executive MBA program. “But they quickly realized that their willingness to engage was way more important than whatever background they had.”

The class had hardly ended and they were already looking for how to take their project forward, Dzombak said. “They cared so much about the outcomes. They cared so much about the work they had put into it.”

Going to the next level

Last year, Gao and Wong brought in another 2021 Cal graduate, Yuquan Zhou, who did her master’s in city planning and whose concentration in environmental planning and healthy cities made her a perfect fit. They were also introduced to Sukh Singh, a researcher at Berkeley’s SCET and co-founder of Fire Foundry, and Thomas Azwell, a Berkeley environmental scientist who runs the Disaster Lab, which is currently focused on wildfire technology. Singh and Azwell had roots in the Marin fire scene and put the trio in touch with fire personnel and Marin County officials.

Wong, meanwhile, discovered a design challenge put out by San Jose social enterprise Wonder Labs: “Reimagining 2025: Living with Fire,” which sought to “enable student-led teams to closely engage with communities in processes of reimagining inclusive, just, and sustainable pathways to living with fire.” Azwell and Singh assisted in their entry proposal, and Rao served as faculty advisor. “One of the reasons I believe in project-based learning is the potential for real-world impact,” Rao said. “I was thrilled that Abby and the team sought out the Wonder Labs competition, and we were excited to leverage the Blum Center’s innovation ecosystem to support them.”

WEmap didn’t win, “but we really appreciated their idea, in particular their community-partnership approach with the Fire Safe program in Marin County,” said Wonder Labs co-founder Shefali Juneja Lakhina. Wonder Labs wanted to see WEmap come to life and find immediate traction in industry. As advisor to Zonehaven, Lakhina knew the company was expanding into Marin County, so she worked with Zonehaven to create a summer project for Gao, Wong, and Zhou. Wonder Labs eventually expanded its 2021 Design Challenge cohort to provide funding support and mentorship to the WEmap project team.

“The project just made so much sense to bring Zonehaven in and not create yet another application. It was a very natural fit,” said CEO Charlie Crocker. “We’re always looking for how to innovate in this space and we found that with this project.”

Bridging the language gap

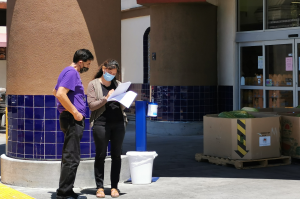

Using census and Wildland Urban Interface data, Gao, Wong, and Zhou found that households with limited English were more concentrated in Marin County’s more fire-prone areas. To hear directly from some of these residents, they homed in on Spanish-speaking San Rafael residents with limited English proficiency and — with the help of Marimar Ochoa, Marin County’s public information specialist, and Sofia Martinez, the county’s diversity, equity and inclusion analyst — they talked to folks at a Spanish-speaking community center, handed out surveys in Spanish, and sent out surveys on Reddit and Facebook groups. The team wanted to understand how these residents received emergency information, obstacles to receiving it, and how they feel and what they do once they have it.

“The biggest takeaway is that English proficiency is highly correlated with how people react and respond to emergency alerts,” they wrote. Simply translating an alert into another language isn’t always enough to deliver the vital information or prompt the desired action.

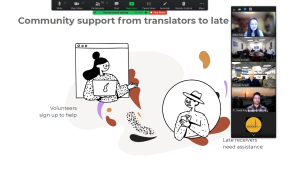

Out of these realizations came recommendations for Zonehaven to incorporate into their platform: understanding residents’ language preferences within the evacuation zones that Zonehaven divides communities into, and making emergency information available in those zones’ preferred languages. They also recommended including actionable resources in emergency alerts, providing a form for residents to sign up for non-emergency assistance in their preferred language, and providing opportunities for community volunteers to translate pressing information and become key nodes between emergency personnel and residents who are on the information-pipeline fringes.

One of the most interesting findings of the WEmap survey, Azwell said, was “most people rely on a friend or family member for critical information — who probably relies on another friend or family member, who relies on another one.” Working with the most connected individuals in communities, Singh pointed out, is why Marin County’s eligible Latinx residents are closing in on a 100-percent vaccination rate. Putting translation into community members’ hands adds nuance and cultural fluency that might be lost in a Google Translate version.

“I think the project has been a good example of true convergence research that applied disciplinary expertise to real-world problems by enabling an industry partner, Zonehaven, to improve their offerings and bringing in community experiences, perspectives, and insights,” Lakhina said. “And I think the timing of the project and the partnerships that it’s built on are truly a lasting contribution, both in terms of developing industry best practices as well as developing community capacities to respond to more just and inclusive evacuation planning.”

Rao celebrated the team’s journey, moving from the class in Spring 2020 to presenting their final work in front of Marin County civic leaders in August 2021. “Here is a team that took a very early stage concept from our course, used research data they collected to reframe the opportunity multiple times, and partnered with a dynamic startup to take their project to the next level and address an overlooked community need. They used the tools of design to execute at a high level and bring in key government stakeholders. This is the work we love to do at the Blum Center, and I’m so thrilled for what the team has accomplished.”

‘Creating a conversation’

WEmap and its partnerships and collaborations, Lakhina added, have established a robust methodology and foundation for developing these kinds of insights, which can be used to tackle other gaps in community-driven and inclusive disaster response, such as for those with disabilities and in places with poor internet.

“This is not something that we want to encourage students or research teams to sit in their labs and develop, but to get out there, work with industry partners, and co-develop with communities,” Lakhina said. “I think that is the single largest learning from this project.”

“This project really helps create a conversation within the disaster-response area that equity and cultural consideration are also worth focusing on, rather than just understanding the severity of fire and where the fire personnel are,” said Wong. “For us, it’s a new way of thinking about a problem, and I think we achieve it: trying to create a conversation in this industry.”