https://mailchi.mp/berkeley/blum-center-newsletter-may-1283857

Category: Uncategorized

Summer 2015

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/Summer%202015%20Newsletter.pdf

Spring 2015

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/Spring%202015%20Newsletter.pdf

Winter 2014

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Winter%202014%20Blum%20newsletter.pdf

Fall 2014

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/BlumCenterFall2014Newsletter.Final.pdf

Spring 2014

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Spring-2014-Newsletter.pdf

Winter 2013

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Winter-2013-Newslettersmallpdf.com_.pdf

Summer 2013

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Summer-2013-Newsletter.pdf

Winter 2012

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/blumcenter_newsletter_2012_winter.pdf

Fall 2012

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/blumcenter_newsletter_2012_fall.pdf

Spring 2012

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/blumcenter_newsletter_2012_april.pdf

Fall 2009

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/blumcenter_newsletter_2009_fall.pdf

Fall 2008

http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/blumcenter_newsletter_2008_fall.pdf

Stephany Martinez Tiffer

worked on issues of sexual and reproductive rights in Nicaragua with the organziation Centro De Mujeres Ixchen

Estrella Sainburg

worked in Chiapas, Mexico with Fundación Cántaro Azul focusing on issues with water filtration, treatment, & drinking water distribution

Elizabeth Cho

completed her practice with Uganda Development Health Associates, supporting programs for individuals with HIV/AIDS

Danielle Puretz

worked in New Orleans, LA with Young Aspirations/Young Artists, engaging youth in public awareness and social engagement through art.

Asia Tallino

worked in Senegal, Africa with Urban Farmers GIE, assisting the organization with fundraising as well as researching urban agricultural practices

Janine Myint

completed her practice experience in Mumbai, India with the Bombay Leprosy Project working to provide specialized care to those diagnosed with the disease

Here Versus There: Reflections from a “Voluntourist”

(Published in the San Francisco Chronicle) By Brenna Alexander Despite the altruistic lure of international volunteering, those seeking meaningful work should look no further than their own backyard. Last summer, I taught and played and laughed with children cooped up in a Cambodian orphanage. I had gone to Cambodia to work for another nonprofit organization. …

While there is much to learn abroad, volunteering at home is different and usually far more beneficial. If you volunteer at home, you are constantly reminded of the persistence of human suffering and the incredible difficulty of generating economic and societal change. When you volunteer at home, you encounter the injustice that resides within your own community – injustices that may collapse long-held notions and the allure of simple solutions.

Brenda Hernandez

worked in the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan, India with the Bhoruka Charitable Trust’s Health of Urban Poor program.

Samantha Dizon

worked with Gawad Kalinga in the Philippines last summer on issues of women empowerment.

Chelsea Harmon

completed her practice experience with TECHO assisting with community development programs in Santiago, Chile.

Esther Chung

worked with the Uganda Village project on health care initiatives and preventative public health education.

Brenna Alexander

worked on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs as well as volunteered with an orphanage in Cambodia last summer.

Christopher Buoy

completed his practice in Cambodia last summer, working on an HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention program.

Christopher Carson

interned with Virtus (Виртус), a non-profit organization in the Ukraine to prevent the spread of HIV and aids.

USAID

Carries out U.S. foreign policy by promoting broad-scale human progress and while expanding stable, free societies.

UC San Francisco

Dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions.

UC Davis Blum Center

A leader in research, theory and applied science in Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources, Energy, Public Health, and Entrepreneurship.

Lawrence Berkeley Lab

A member of the national laboratory system supported by the United States Department of Energy through its Office of Science.

Global Social Venture Competition

Provides aspiring entrepreneurs with mentoring, exposure, and prizes to transform their ideas into businesses that will have positive impact.

Center for Effective Global Action

The University of California’s premiere center for research on global development.

Development Impact Lab (DIL)

Draws on innovative methods to identify, refine, evaluate, and scale new solutions, with a focus on long-term sustainability and affordability.

Technology and Infrastructure for Emerging Regions

Focuses on developing a hardware/software infrastructure designed for developing areas.

Crystal Cantabrana

Completed her practice with Nest, a nonprofit microbartering and fair trade organization in Nairobi, Kenya.

Arienne Malekmadani

Completed her practice with Blue-Med Africa in Ghana. She shadowed doctors, and assisted with patient intake and outtake.

Angela Roh

Completed her Practice in Trichy, India working with Nest, a nonprofit microbartering and fair trade organization.

Nikki Brand

Completed her Practice in Panajachel, Guatemala where she worked with Nest, a nonprofit microbartering and fair trade organization.

Shahrzad Makaremi

Shahrzad completed her Practice with Sambhali Trust in Jodhpur, India to support the education and empowerment of lower-caste women.

Julia Hurwitz

Completed her Practice in Togo, Western Africa where she worked with Nest, a nonprofit microbartering and fair trade organization.

Danika Kehlet

Completed her Practice in Quito, Ecuador where she worked in a reproductive health clinic and assisted with sexual and reproductive health education.

Kelsey McCarthy

Completed her Practice in Cape Coast, Ghana where she worked with the Rural Women Development and Health Initiative.

Microclinics International

The Challenge

In impoverished and war-torn areas, regional instability leads to ineffective health care infrastructure unable to adequately treat ailments such as diabetes and HIV/AIDS.

The Technology Approach

Through community-based workshops, micro-clinics leverage social networks to spread “contagious health” best practices, providing information dissemination and training in conjunction with local partners.

2013 Updates

The NGO MicroClinics International will expand and support the 1,500 established micro-clinics spanning four continents through evaluation and policy advocacy. The group also recently launched a diabetes micro-clinic project domestically in Kentucky.

Principal Investigator

Prof. Eva Harris, School of Public Health

Lead Researcher

Daniel Zoughbie, Principal Investigator, CEO Microclinic International

[button link=”http://microclinics.org/” text=”Website”]

Lumina Project

LED Lighting

The Challenge

Over a billion people in the developing world lack access to an electric grid and instead rely on inefficient, expensive and polluting flame-based lighting.

The Technology Approach

The Lumina Project works through laboratory and field-based investigations to cultivate technologies and markets for safe, affordable lighting options that can replace fuel-based options in the developing world, including low-carbon alternatives, such as LED lighting.

2013 Updates

In addition to supporting various off-grid lighting projects in Africa, the Lumina Project team has recently conducted in-depth studies of the health impacts of fuel-based lighting, in addition to market analysis regarding carbon credit mechanisms in the developing world.

Principal Investigator

Dr. Evan Mills, Building Technology and Urban Systems Department, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

[button link=”http://light.lbl.gov/” text=”Website”]

ReadyMade Impact Assessment

The Challenge

Social organizations frequently lack the resources and expertise to assess the impact of their programs to guide future growth, as the opportunity costs of assessments are high and may result in little value added to the organization unless done in a meaningful way.

The Technology Approach

ReadyMade provides social enterprises a free and effective online tool to aid in assessment of impact and costs through analysis of essential data that are easy to collect.

2013 Updates

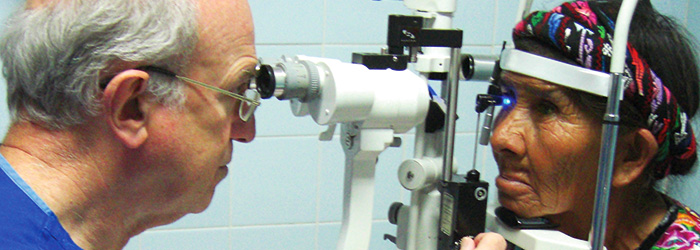

ReadyMade will develop an online impact assessment tool that can be used by organizations to undertake assessments, track project outcomes, and create evaluation reports. The team has developed prototypes in a variety of areas, including a cataract surgery clinic, agricultural co-ops in Africa and Asia, and at-risk youth college-prep program in the US.

Lead Researcher

Prof. Clair Brown, Economics

Field Locations

Prototypes in South America, Africa, Asia, and United States

Prototype Reports

Developing an Effective and Efficient Assessment Template for Social Enterprises

Analysis of Berkeley Scholars to Cal Program

Hospital de la Familia’s Cataract Surgery Program in Guatemala

Village Base Station

A Cellular System for Rural Off-Grid Locations

The Challenge

Over one billion people in rural areas worldwide lack access to the transformative technology of cellular phones.

The Technology Approach

The Village Base Station (VBTS) cellular tower is optimized for rural, off-grid deployments by drastically reducing the cost of cellular coverage through decreased required power, especially when not in active use.

2013 Updates

The VBTS is deploying three towers in rural Papua, Indonesia, aiming to serve between 1,000 and 10,000 people.

Lead Researchers

Prof. Eric Brewer, Computer Science

Prof. Tapan Parikh, School of Information

Field Location

Indonesia

[button link=”http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/~kheimerl/pubs/vbts_nsdr10.pdf” text=”White Paper”]

Darfur Stove Project

Fuel Efficient Stoves for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

The Challenge

Since 2003, civil conflict in Darfur has led to massive displacement of people into densely populated camps. The Darfur Stoves Project provides Darfuri women with specially developed cookstoves that require less firewood, reduce pollution, and decrease women’s need to trade food rations for fuel and their exposure to violence by reducing the time needed to collect needed firewood.

The Technology Approach

The stoves team leads the development of fuel efficient stoves through user-centered design, reducing both harmful emissions and firewood collection by 50% each. For a family, the stove leads to up to $1770 in firewood savings over five years.

2013 Updates

Started at Lawrence Hall of Science (LBNL), the project is currently also the first initiative of Potential Energy, a Berkeley-based, independent nonprofit organization whose mission is to bring life-improving household technologies to women in the developing world. Potential Energy is transitioning to a market-based approach in Darfur and is partnering with LBNL to design a fuel-efficient stove for use in Ethiopia.

Lead Researcher

Dr. Ashok Gadgil, LBNL

Field Locations

Darfur, Sudan; Ethiopia

[button link=”http://www.potentialenergy.org/” text=”Website”]