Education has long been considered a means to move out of poverty. Edtech—teaching and learning that makes use of technology—has in recent years become a multi-billion dollar sector for both developed and developing countries. And an emerging category in the sector are nonprofit organizations, backed by investors eager to spread tech literacy to improve livelihoods throughout the globe.

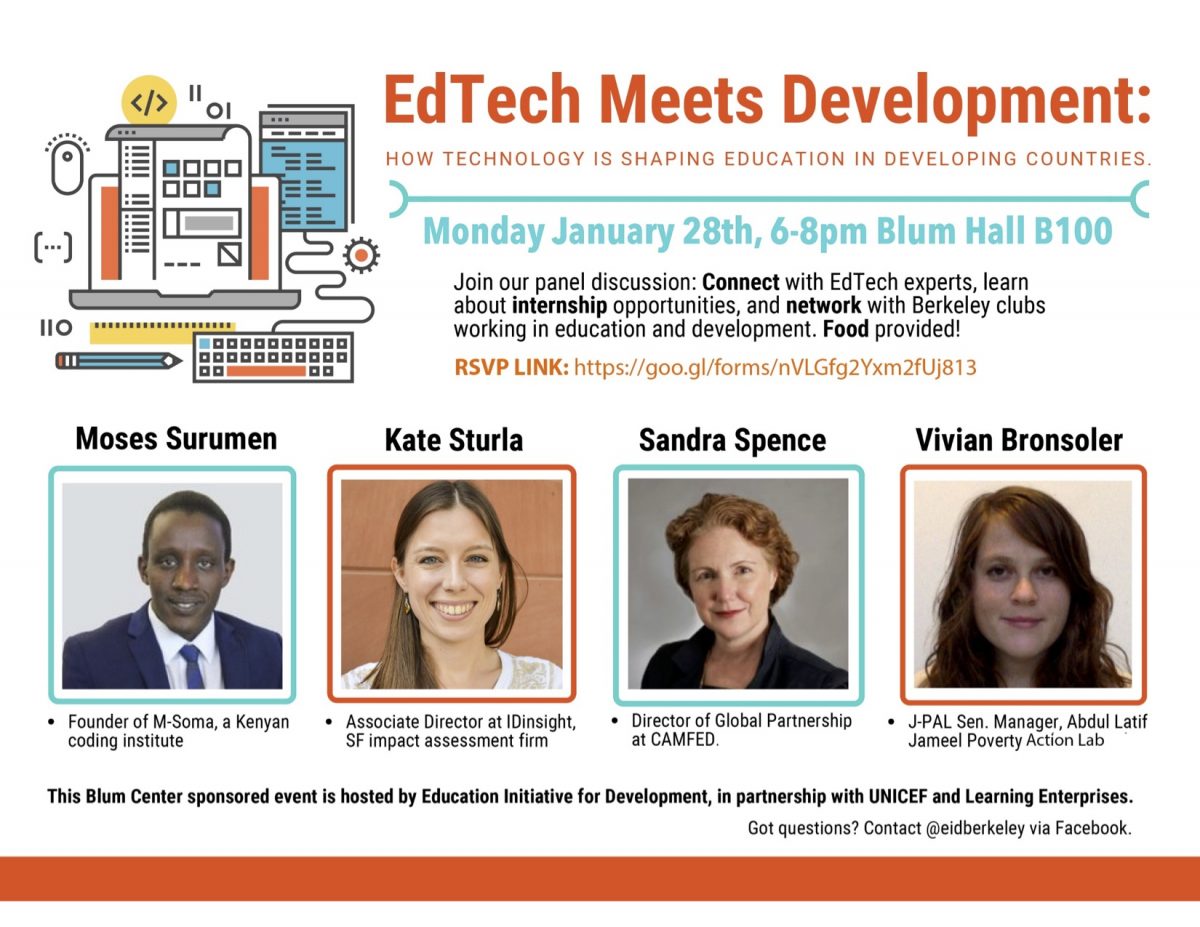

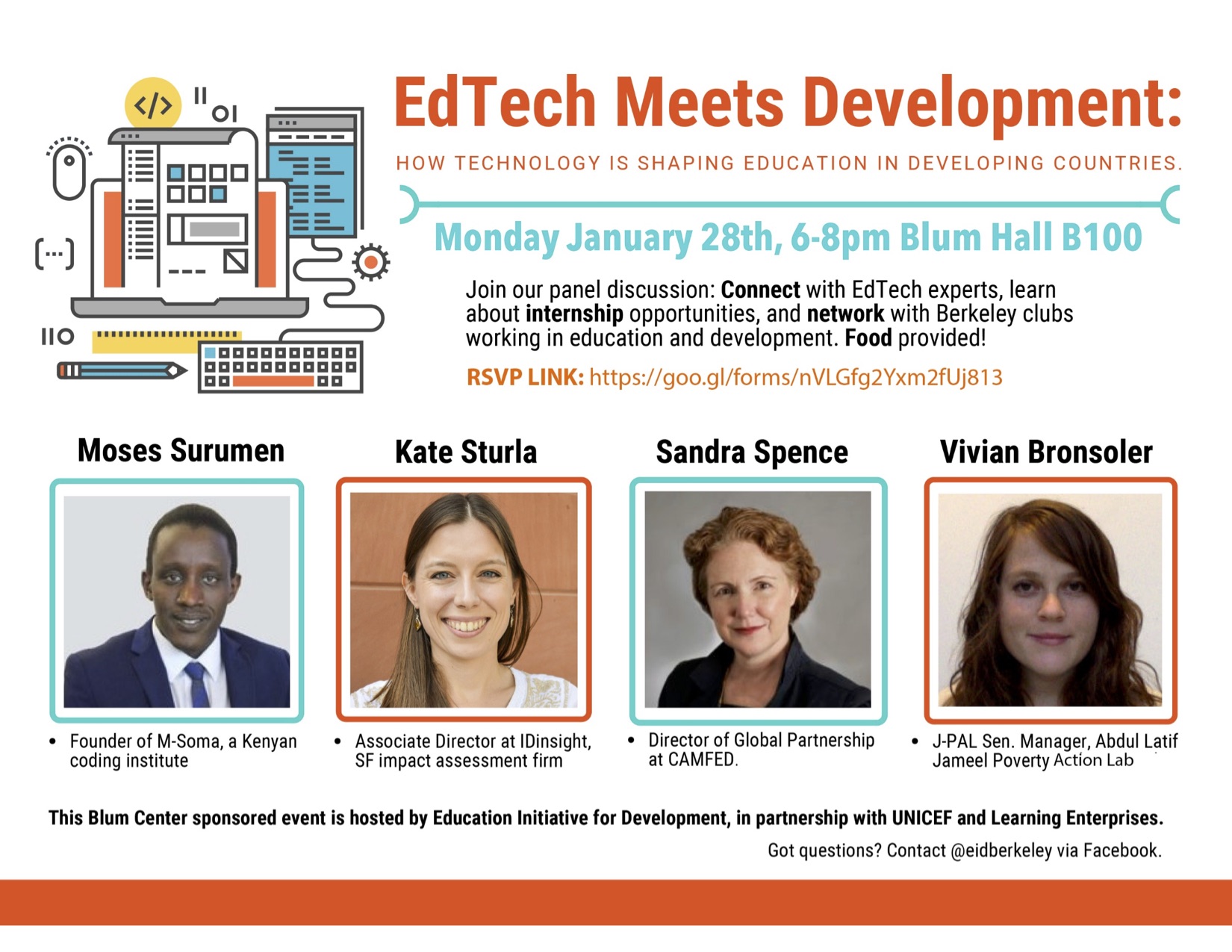

On January 28, Berkeley’s Education Initiative for Development (EID) IdeaLab, a group of interdisciplinary undergraduate and graduate students passionate about education and development, hosted four nonprofit education technology professionals to spark dialogue and provide updates on edtech’s evolution. Three of the panelists graduated from UC Berkeley and one is a current student.

The panelists included:

Kate Sturla (B.A. ‘09) associate director of IDinsight, a San Francisco-based impact assessment firm that uses data and evidence to help leaders combat poverty worldwide. Sturla manages projects in education, health, and agriculture.

Moses Surumen (B.S. ‘19), a fourth-year Cal engineering and computer science student, is founder of the Kenyan coding institute M-Soma, which teaches Kenyan high school students computer science. M-Soma currently instructs a cohort of 47 students.

Sandra Spence (MPH ‘09) is a UC Berkeley School of Public Health graduate and director of global partnerships for CAMFED, a nonprofit whose mission is to eradicate poverty in Africa through the education of girls and the empowerment of young women.

Vivian Bronsoler (MPP ‘14) is senior manager of J-Pal (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab), a nonprofit global research center based at MIT devoted to reducing poverty by ensuring that policy is informed by scientific evidence. With a network of 171 professors at universities around the world, J-PAL conducts randomized impact evaluations to answer questions in the fight against poverty.

The EID panel, moderated by student Paige Balcom, focused on common pitfalls of edtech to inform students about new directions in the field.

How is technology being used to support education in developing countries? How is it different urban or rural areas?

Kate Sturla: Edtech often operates in resource-poor environments—schools may not even have chairs or tables, let alone electricity. So we must be cognizant not only of physical limitations, but also that there is a thoughtful theory of change mapped out for any given edtech intervention.

Sandra Spence: When CAMFED started thinking about incorporating tech in schools, we knew it had to be very basic, especially in rural schools. In Malawi, we gave each school e-readers. The schools were able to negotiate the rights to get books for a discounted rate, which increased student exposure. In the beginning, the schools were scared the Kindles would be broken or stolen and it was hard for students to electrically charge the ebook. We encountered several hurdles to making the technology practical as we moved along.

Vivian Bronsoler: Technology can be used in innovative ways, but we have to be careful. Technology should not be a substitute for teaching or for cognitive practices while studying. For example, One Laptop Per Child [a nonprofit that creates and distributes educational devices for the developing world] had a broad goal to teach kids how to use computers. However, it hasn’t helped student learning or attainment of knowledge—it’s not a substitute. In other words, technology should be seen as a complement to teaching.

For example, technology can be helpful in less obvious ways that simplify the process of education. A website could could allow students to access homework assignments online, or a database could organize scholarships resources. A teacher could use an app to take attendance for large classes, and keep better track of grades—while parents could also access this information to be more involved in their child’s education.

What is a common misunderstanding people have about edtech in developing countries?

Sandra Spence: You can’t just drop technologies into an environment. You need to ask: What is the human platform that will support it?

Kate Sturla: People often conflate computer literacy skills with edtech. For example, access to computers can help students become more literate in how to actually use the device (i.e., typing) versus helping a student actually learn a subject, like math. We should also make sure we teach at the correct level and give teachers the tools to target students at different learning levels.

Vivian Bronsoler: Edtech is attractive to people who want quick solutions—it can seem like a solution, but money can often be better spent better somewhere else. It’s wrong to copy and paste an intervention from one context to another or say you have an innovative idea without actually testing it.

How do you think Berkeley students can make a difference in edtech?

Moses Surumen: Take an education class. We can’t develop apps without understanding of how people learn.

Vivian Bronsoler: During your college career, you learn the tools and theories to get trained on various poverty interventions. But then, once you are in the professional world, various realities exists and challenges arise. Volunteer anywhere you can to get some real-world experience—really be engaged. Learn as much as you can— you can use it in practice.

Sandra Spence: Don’t get swept away by technology. Be part of the wave that is thoughtful about the application of technology. Ask: How does technology fit into the environment? Is it empowering? Are you listening to the people closest to the problem?

Kate Sturla: IDinsight began as a graduate project. Being a student is the best time to build bridges across disciplines and majors and take classes to get different perspectives. Push yourself to take a class outside of your major to get a different angle.

Interested in joining the Education Initiative for Development IdeaLab? Contact IdeaLab Co-Directors Samuel Cabrera (samuel_cabrera@berkeley.edu) and Bei Zhang (bzhang_1900@berkeley.edu).