Danika Kehlet

Completed her Practice in Quito, Ecuador where she worked in a reproductive health clinic and assisted with sexual and reproductive health education.

University of California, Berkeley

Completed her Practice in Quito, Ecuador where she worked in a reproductive health clinic and assisted with sexual and reproductive health education.

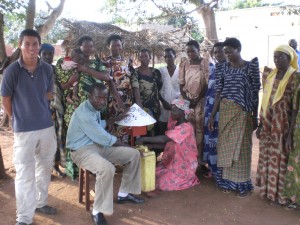

Completed her Practice in Cape Coast, Ghana where she worked with the Rural Women Development and Health Initiative.

In impoverished and war-torn areas, regional instability leads to ineffective health care infrastructure unable to adequately treat ailments such as diabetes and HIV/AIDS.

Through community-based workshops, micro-clinics leverage social networks to spread “contagious health” best practices, providing information dissemination and training in conjunction with local partners.

The NGO MicroClinics International will expand and support the 1,500 established micro-clinics spanning four continents through evaluation and policy advocacy. The group also recently launched a diabetes micro-clinic project domestically in Kentucky.

Prof. Eva Harris, School of Public Health

Daniel Zoughbie, Principal Investigator, CEO Microclinic International

[button link=”http://microclinics.org/” text=”Website”]

Over a billion people in the developing world lack access to an electric grid and instead rely on inefficient, expensive and polluting flame-based lighting.

The Lumina Project works through laboratory and field-based investigations to cultivate technologies and markets for safe, affordable lighting options that can replace fuel-based options in the developing world, including low-carbon alternatives, such as LED lighting.

In addition to supporting various off-grid lighting projects in Africa, the Lumina Project team has recently conducted in-depth studies of the health impacts of fuel-based lighting, in addition to market analysis regarding carbon credit mechanisms in the developing world.

Dr. Evan Mills, Building Technology and Urban Systems Department, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

[button link=”http://light.lbl.gov/” text=”Website”]

Social organizations frequently lack the resources and expertise to assess the impact of their programs to guide future growth, as the opportunity costs of assessments are high and may result in little value added to the organization unless done in a meaningful way.

ReadyMade provides social enterprises a free and effective online tool to aid in assessment of impact and costs through analysis of essential data that are easy to collect.

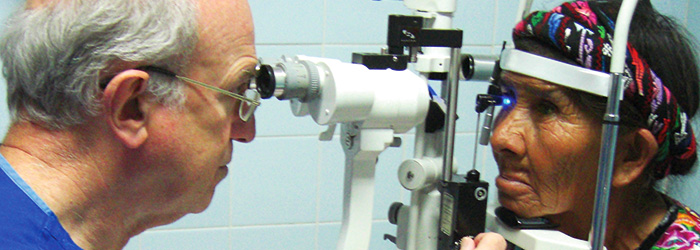

ReadyMade will develop an online impact assessment tool that can be used by organizations to undertake assessments, track project outcomes, and create evaluation reports. The team has developed prototypes in a variety of areas, including a cataract surgery clinic, agricultural co-ops in Africa and Asia, and at-risk youth college-prep program in the US.

Prof. Clair Brown, Economics

Prototypes in South America, Africa, Asia, and United States

Developing an Effective and Efficient Assessment Template for Social Enterprises

Analysis of Berkeley Scholars to Cal Program

Hospital de la Familia’s Cataract Surgery Program in Guatemala

Over one billion people in rural areas worldwide lack access to the transformative technology of cellular phones.

The Village Base Station (VBTS) cellular tower is optimized for rural, off-grid deployments by drastically reducing the cost of cellular coverage through decreased required power, especially when not in active use.

The VBTS is deploying three towers in rural Papua, Indonesia, aiming to serve between 1,000 and 10,000 people.

Prof. Eric Brewer, Computer Science

Prof. Tapan Parikh, School of Information

Indonesia

[button link=”http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/~kheimerl/pubs/vbts_nsdr10.pdf” text=”White Paper”]

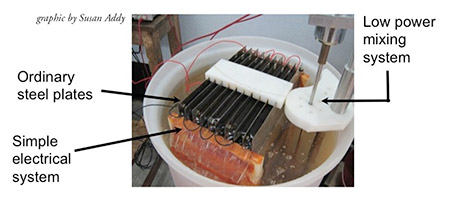

Since 2003, civil conflict in Darfur has led to massive displacement of people into densely populated camps. The Darfur Stoves Project provides Darfuri women with specially developed cookstoves that require less firewood, reduce pollution, and decrease women’s need to trade food rations for fuel and their exposure to violence by reducing the time needed to collect needed firewood.

The stoves team leads the development of fuel efficient stoves through user-centered design, reducing both harmful emissions and firewood collection by 50% each. For a family, the stove leads to up to $1770 in firewood savings over five years.

Started at Lawrence Hall of Science (LBNL), the project is currently also the first initiative of Potential Energy, a Berkeley-based, independent nonprofit organization whose mission is to bring life-improving household technologies to women in the developing world. Potential Energy is transitioning to a market-based approach in Darfur and is partnering with LBNL to design a fuel-efficient stove for use in Ethiopia.

Dr. Ashok Gadgil, LBNL

Darfur, Sudan; Ethiopia

[button link=”http://www.potentialenergy.org/” text=”Website”]

Lack of reliable electricity results in inadequate obstetric care for pregnant mothers and their offspring in the developing world, contributing to morbidity and mortality.

The durable and portable “We Care Solar Suitcase” provides power for medical LED lighting, cell phones, and battery charging for fetal dopplers and headlamps – reducing delays and increasing capacity of providing emergency obstetric care.

We Care Solar aims to expand by deploying networks of Solar Suitcases in specific regions, partnering with Ministries of Health and NGOs to enhance health care delivery. The engineering team is working to improve the suitcase design through increased battery life, higher performance LEDs, and an integrated PC board. Additionally, a recently launched Solar Ambassador program has trained women to lead installations and international trainings.

Laura E. Stachel, MD, MPH, DrPH Candidate

Western, Central, and Eastern Africa; Central America, Haiti, Asia

[button link=”http://wecaresolar.org/” text=”Website”] [button link=”https://www.facebook.com/WeCareSolar” text=”Facebook”]

Since it was established in 2006, the Blum Center has supported green innovation at UC Berkeley and around the world. Both the Big Ideas@Berkeley student competition and various faculty-led initiatives have produced projects that simultaneously improve the lives of individuals and benefit the environment.

Author:

Brittany Schell

Since it was established in 2006, the Blum Center has supported green innovation at UC Berkeley and around the world. Both the Big Ideas@Berkeley student competition and various faculty-led initiatives have produced projects that simultaneously improve the lives of individuals and benefit the environment.

Since the first Earth Day was celebrated on April 22, 1970, the modern environmental movement has taken shape. Over the past four decades, ideas about conservation, energy efficiency, and sustainability have come to the forefront of innovation.

In honor of Earth Day 2012, the Blum Center recognizes the vast array of green ideas that have been realized at UC Berkeley over the years, with the support of the center and other partners—from energy efficient stoves in Darfur, Tanzania and Ghana to a local bike share program, to solar energy projects and a proposal to “green” Berkeley’s campus.

This year, we have a whole new group of student contestants for Big Ideas@Berkeley. The contest winners will be announced on May 1, so stay tuned. For more information on this or any of the projects listed to the right, visit our website: http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu

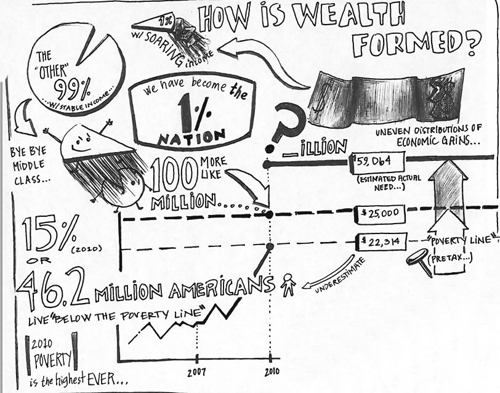

Caliber, a UC Berkeley general interest magazine, featured the #GlobalPOV story artist, Abby VanMuijen, and her popular DeCal course in its Spring 2013 edition (Issue 7). According to VanMuijen:

I like to leave information up in a cloud in my head, and take each piece down one-by-one, and draw it out.

. . .

It’s empowering to turn this hobby into something that other people can use. I really believe that visual notetaking is something that everyone can learn. People from all majors and paths of life take this DeCal, and the class is structured in a way that everyone can gain something out of it.”

To read the full article, click here.

One fall 2011 afternoon, while sitting/doodling/not sleeping in Prof. Roy’s “Global Poverty: Challenges and Hopes in the New Millennium” class, student Abby VanMuijen ditched her live-action note-taking for a moment and scribbled down a series of words instead. (Abby can spell, say wha?) The words were Abby’s response to Thomas Friedman’s “the world is flat” assertion. A year later, her words inspired the #GlobalPOV team, not to mention our logo:

And all this time, I thought the world was round.

The world is not round.

It has edges we can fall from and faces staring

in entirely different directions.

And I thought the world was huge, but it is not — it’s in our hands.

We can hold it, change it, turn it, shake it.

We can solve it, but not by sheer luck or chance.

We must be taught the way.”— Abby VanMuijen, U.C. Berkeley ’12

Nicole helped organize a group of youth to interview and survey families in the community in order to gather information that would help them decide what types of development projects would be useful.

Major: Architecture

Year of Graduation: 2009

Location and date of Field Experience: Salvador, Brazil (July – August 2008)

Organization: Axis Mundi Design

Project: A participatory design/build project for a marginalized settlement on the outskirts of Salvador

Hometown: Laguna Nigel, CA

Quote: To this day, I feel like I’ve been given so many opportunities because of the minor. I love the fact that everyone has their own academic and professional goals and then finds a way to integrate development work within that framework.

Tell us a story from your practice experience.

I worked with a small group to design and build a public outdoor seating area using a participatory design process. We wanted to involve the community members in every phase of the project — choosing the location, creating the design and constructing the actual project — through this process we really wanted to understand how the project could improve their living environment. After spending time with the community, we saw everyone gravitating towards a beautiful space with a view of the ocean — the kids played games, the women conversed while hanging their laundry, others played music or just enjoyed the view. We noticed that everyone sat on the ground or random pots or boxes. After drawing sketches with community members about project ideas for this location, we decided to build a concrete table with a system of overlapping benches.

Music is huge in Brazil. People are always drumming on things. We decided to build the table and benches with a built-in drum so that the kids could make music when they played on them. We put an old pot inside a concrete bench and the kids all signed their names on it. We also designed the structure to have poles with hooks so it could be integrated into the laundry system that the women already used the space for. They could hang their sheets and clothes to dry and shade themselves simultaneously.

The best part was seeing everyone help with various parts of the project; from mixing concrete, carrying gravel or helping us make the formwork for the benches, we were constantly engaging with and learning from one another. Once the project was complete, the community members threw a party with music and food. Everyone seemed so excited and welcoming. I will never forget the next day when we woke up to see kids playing on and around the structure and using the table to draw and write. Throughout the day we saw women hanging their laundry as we had hoped and various community members congregated there to play music, talk or just enjoy the day. The project really felt like a success and I will never forget the experiences I had there.

What’s something that the Global Poverty and Practice minor taught you that has influenced the work you hope to do?

To this day, I feel like I’ve been given so many opportunities because of the minor. I love the fact that everyone has their own academic and professional goals and then finds a way to integrate development work within that framework. The GPP minor is a great starting place to learn about and develop critical analytical skills to target pressing issues worldwide. Students from the GPP minor are innovators, paving the way for their self-defined careers and futures. Once I got involved in it, all of these opportunities kept coming my way and the Blum Center always provided their support. And it was with the support of professors like Ananya Roy that I received a Fulbright grant to do research in Guatemala.

Tell us about your Fulbright project.

We used a participatory analysis process to coordinate community development projects in a rural Guatemalan community. After my project in Brazil, I knew I wanted to understand how to better engage communities in the development of their environment. We went through an intensive process of community meetings, surveys, semi-structured interviews, and community mobilizing in order to really understand the needs and strengths of the community. We mutually decided on developing three project scopes, each of which would address specific needs expressed throughout this participatory appraisal process.

The small scale project is to revamp an old building into an information center with computers, a library and an area to give workshops. We wanted it to be a place where the community could connect with the rest of Guatemala and access information and communication resources. For example, we suggested that local coffee farmers could use the Internet to network directly with their buyers and cut out the middle man.

The medium scale project is to help organize a women’s cooperative to start a bakery. During our meetings, women had emphasized their interest in making money for themselves as well as learning new recipes. We agreed that a bread cooperative would be beneficial for them, seeing as they currently buy bread from another community. But again, a project like this one is complex — more than we could have ever initially thought. We had to think about how to grow or buy wheat, what the altitude might permit, the soil, an oven, the skills that each woman could bring to the business as well as trainings for them to learn how to keep finances or sign their names… again, so many details.

The largest and by far the most difficult undertaking is constructing water infrastructure. The nearest water source is two hours away by foot, making it difficult for engineers to map the route, think about a pump system and electricity, where water stations will be placed, drainage, the cost of water and even politics! The minor opens your eyes to the intricacy and massiveness of every project. Nothing is black and white and there are a lot of complex pieces to this work.

What is your dream job?

I don’t know if I have a dream job in mind yet. I want to be someplace where I can expand and improve development programs and interventions. I’d love to apply for an internship at UNDP or USAID. I feel like so many already established programs are not effective and that resources are lost between these institutions and the community or non-profit they are intending to serve. I’d like to find somewhere in between where I could help resources be more well delivered.

What are you doing now?

I applied to graduate school for urban planning with a focus on International Development and will be going to UCLA (on a full-ride scholarship!) starting this fall. This summer, I participated in the Global Health and Women’s Empowerment institute at UCLA. It was one of the most stimulating classes I have every taken and I can’t wait to get more involved in such work. I’ve also been working to develop a student organization called Amazon Medical Program to bring UCLA students to the Brazilian Amazon to work with a nonprofit there who delivers health services to isolated communities along the Amazon River.

Lisa did in-house water quality observations to understand how water is contaminated in a slum in Mumbai, India.

Major: Civil and Environmental Engineering

Year of Graduation: 2010

Location and date of Field Experience: India, Summer 2010

Organization: Hath Mein Sehat

Project: in-house water quality observations and NGO development

Hometown: Oak Park, CA

Current Location: Penrin– small suburb of sacramento– moving to Los Altos soon to start a job as an environmental educator!

Quote: The minor got me to feel comfortable with being uncomfortable. It’s why I’m challenging myself in ways I wouldn’t have been able to before.

Tell us about your practice experience.

The first summer I went to India was in 2010 and I went to Mumbai. We did in-house water quality observations to understand how water is contaminated in a slum. It was a combined research project: ethnographic, but also biological. We got to work closely with so many families– to break language barriers with student speakers and go into a lot of places that we wouldn’t have been able to go otherwise. Having the “GPP badge” gave us the opportunity to inhabit so many different places and be incredibly mobile.

The second summer I went (2011), we were in a very different place. We went to Hubli in the south and were doing a lot of NGO development. We hired a new staff member, developed our program further and worked to increase the organization’s legitimacy. This coming summer, our NGO will be three years old. It’s so exciting to see this infant organization operating and growing out of our hands, especially when we were so closely holding its hand just a year ago.

Who was the most interesting or inspirational person you met during your practice experience? What did they teach you?

We went to this very modern cafe in rural India (which was totally weird and entirely different than everything else in the town). We started theorizing and coming up with strategies about how to go about our project (as cafe-dwelling Berkeley students often do). Suddenly we thought to ourselves, “Who owns this place?” It was so different from what we had seen and it felt almost out of place, and yet it was incredibly popular with the young, hip local crowd.

We actually ended up becoming close friends with the owner, who was the same age as me. “I just love coffee and I love cafes,” he said to us. He was native Hubli born, had his Master’s Degree and decided at age 23 that he wanted to start his own cafe. His approach to it all was incredible. He was down to earth, but was very well versed in business practices. His whole plan was well thought out and organized, and he obviously had a lot of passion for this venture–I really admire him.

How has the Global Poverty and Practice minor affected your goals and what you hope to accomplish?

The minor got me to feel comfortable with being uncomfortable. That’s the essence of what you get after doing your practice. That’s what made me want to come out here and apply for the Fulbright. It’s why I’m challenging myself in ways I wouldn’t have been able to before. The minor has opened a lot of doors for me. It’s a little selfish because I get to go work abroad and take classes that criticize development, but now I see so much potential for international collaboration if you have international experience. The minor gave me a lot of great perspective for that. I feel incredibly lucky to have been given a chance to take advantage of it.

It has also shown me just how important it is to be passionate. After leaving the minor, I’ve started to realize that a lot of the systems I’ve put into place for myself just aren’t paralleled by a lot of people. It’s hard to get people to talk about things they care about– there’s no passion. Especially coming from an engineering background. Engineering curriculum is so dry and a little ridiculous in my opinion. There’s just no social training or exposure. Engineering majors need to take these (GPP) classes. I think we all need to learn a lot more before we go out into the world and think we can solve problems with an equation.

What are you doing now?

I’m currently living and working on a farm. I rise and sleep with the sun, and have the luxury of being distraction-free, in which I spend my time cooking, writing, reading, reflecting, and playing music. So many people spend hours of precious daylight just commuting to and from work, but if you live where you work and grow your own food, it’s hard to find a reason to leave the land.

What is your dream job?

To be a salsa singer/farmer/teacher– being outdoors with music and young people.

Farrah helped to build a rain-water harvesting system on top of the latrines that was then used to make a hand-washing station.

Major: Political Economy

Year of Graduation: Spring 2012

Location and date of Field Experience: Tanzania, Summer 2011

Organization: African Immigrant Social and Cultural Services

Project Description: Initiate the planning, preparation, and implementation of a bread oven in the region.

Hometown: New Delhi, India and Anahiem Hills, CA

Current Location: Berkeley, CA

Quote: I knew that I wanted to work on global poverty issues for my whole life, so when I heard about the minor, I thought, “Cool, this is an opportunity to get some academic training in this area I’m passionate about!”

Could you describe your practice experience?

I went to Tanzania specifically to work on a bread oven project, but things totally changed when I got there. We ended up working on large rainwater harvesting tins, latrines, we built a chicken coop and made a children’s gymnastics dome-type structure… That was one of the most important things I learned: what you sign up for isn’t necessarily what you’re going to get. I think that’s probably something really common in global development– it’s not really something you can teach, you more so have to experience it.

What was one significant challenge you faced?

I’d say that my “narrow vision” was a problem I frequently had to deal with. Even having grown up partly in a developing country, there were still a lot of things that I forgot and took for granted. My eyes were opened… I was shocked when I had a side conversation with a woman who asked me about contraception. She was a mother of 10 and didn’t want to have any more children. Before that conversation, I had known she was a mother of 10 but hadn’t really thought much about it. In that moment I realized, “Oh my God, if she had any control over the situation, she would probably not have 10 children…” There are so many intertwining issues that I had never thought about– so many things that were daily life challenges that I had to be beaten over the head with before I really understood.

Describe one interesting and/or inspirational person you encountered.

The founder of the organization, Christine Chacha, was a Swahili professor born and raised in the village area we were working in. She actually passed away a few months ago from cancer, but she was the reason I was attracted to the organization. She understood both foreign and local cultures and could bridge the gap between the two by using what both sides had to offer. She was so full of life and so amazing in her ability to work with and get cooperation from people of all types in the village. She would shame lazy workers, but then hug any small child around. She would sing and dance around the house. Even though she was sick, she was such a force of life. It was an honor to be around her and I am so grateful to have had that time with her.

How has the GPP minor influenced your plans for the future?

I am now forced to question the structure within which I’m working– especially now that I’m working from a grant-giving side. I’ll be critical of the criteria we’re using to evaluate things: Is this the most efficient way to accomplish something? How was it conceived and organized?

Becoming really critical has become my greatest gift from the minor and I hope that stays with me forever. It has changed me so much in terms of how I think about how the world got to be the way it is, which I think is really important to be conscious of if you want to be a part of changing the world into something else.

Benjamin Hans spoke with village leaders to a community about chlorine dispensers in Iganga, Uganda.

Major: Industrial Engineering and Operations Research

Location and date of Field Experience: Uganda, Summer 2009

Organization: Engineers for a Sustainable World

Project Description: Improving water quality and reducing disease

Hometown: Redlands, CA

Current Location: Rwanda

Quote: I am driven to bridge the gap between people and their dreams.

What did you do for your practice experience?

There were two projects:

Project #1: We launched a safe water pots program. The village was storing their drinking water in ceramic pots, which helped to keep it cool, but when they went to scoop water out of the pots with a cup, if they touched the water, it was very possible it would be contaminated. We designed a pot with a spigot to limit that contamination.

Project #2: We installed chlorine dispensers next to the wells where the villagers pumped their water. The dispensers dropped 1 ml of chlorine into a bucket of water to kill of any bacteria in it. I thought this project was more interesting than the first one because we got the opportunity to work with the entire village. We had to find a way to communicate that this was a project that would require everyone to pitch in with and learn how to use.

It’s been really amazing to see this project ramp up. We started off installing 5 dispensers in Uganda and currently, the same organization is working on a project to instal 1,000 dispensers in Kenya.

Describe an inspiring person you met during your practice experience.

Our translator Edward became very close to our team. I remember one night, it was a beautiful night in Uganda and you could see all the stars– but he was telling me about his dream to start a primary school. He had gone to the university, gotten his education and had all of these ideas about how he could make a great school to educate the youth in the area. He was trying to get the money to do it and had applied to the government to get the seed money to start this school, but was having no luck.

Here I was, standing next to this man with a great education, a great heart and a passion for wanting to help people, but he couldn’t get his idea off of the ground because there was just no legitimate opportunity for him to access the capital to get it off the ground. That had a huge impact on me– he was someone with so much potential to do great things, but he was entirely limited by his environment and access to opportunity. It got me thinking about how so many people that I meet have dreams and the drive to accomplish them, but because of external factors, they may never be able to get there. We talk a lot about gaps we’re trying to bridge, but Edward made me realize that I am driven to try to bridge that gap– the one between people and their dreams.

If you had one piece of advice for current Global Poverty and Practice minors, what would it be?

I don’t remember all of the facts or the numbers about how many people in India don’t have access to clean water… But the two things I value and will remember most from the minor are:

One thing college grads should understand is that its difficult to break into the development field and actually apply what you’re studying, but at the end of the day it’s possible if you stick to what you’re interested in.

To celebrate the end of an extremely experimental stressful successful semester, the “Global Poverty” course graduate student instructors (all 482 of them) and the #GlobalPOV team came together to eat, drink and be merry. But then Bono showed up, per usual, and Prof. Roy promptly kicked all of us out of the house so the two of them could be alone, per usual. Some party.

(And yes, bunny ears are still socially acceptable at academic functions. Just to clarify.)

The #GlobalPOV Project’s in-class tweeting component was covered in the Fall 2012 edition of the Blum Center newsletter. In the article, writer Javier Kordi notes:

Chipping away at the tradition of hierarchical education, the Twitter project restructures social relations within the classroom.

. . .

Being a public medium, Twitter allows anyone to join the conversation, but also forces Berkeley students to think of themselves as public scholars— everything they post falls under the scrutiny of the global community.”

To read the full article, click here.

The #GlobalPOV Project’s story artist, Abby VanMuijen, and her live-action sketch skillz were covered in the Fall 2012 edition of the Blum Center newsletter. As a student, VanMuijen doodled her way to producing The Global Poverty Coloring Book, which students now use as a learning aid in Prof. Roy’s Global Poverty class. In addition to now working as our story artist extraordinaire, VanMuijen is teaching a DeCal class, titled “Visual Notetaking 101,” which attracts 150 students from departments all over campus. According to VanMuijen:

I wasn’t magically bestowed with the ability to take notes the way I do. It was something I practiced every day, and taught myself how to do. I started “Visual Notetaking 101″ because I realized this is a skill that people can learn. Visual notetaking can revolutionize your entire outlook on your education, as it did for me. Seeing your thoughts and ideas and opinions come to life, even if just on paper, is empowering.”

To read the full article, click here.

Prof. Roy yacked on and on about Bono. Abby did some doodling. Tara shoved a camera in everyone’s face. This vid resulted. Take a behind-the-scenes look into the making of The #GlobalPOV Project’s “Who Sees Poverty?” pilot video.

[youtube id=”yFuAjlqL9Ps”]

Continue reading “Blast Off! Launching The #GlobalPOV Project Vid Series”

Kristin Hanes, a reporter with KGO Radio, visited Prof. Ananya Roy’s “Global Poverty: Challenges and Hopes In The New Millennium” class this week to explore and experience Roy’s use of Twitter as a teaching tool. Hanes interviewed Roy and talked to students during class (tisk! tisk!) to get their feedback on the process. According to Hanes:

Students in a Global Poverty lecture at UC Berkeley are incorporating Twitter into class, which gives shy students a voice, and expands interactions in a class of 600.

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference.

Author:

Luis Flores

“We’re doing research in reverse,” explained student researcher Stephanie Ullrich. “We’re going from practice to theory.”

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference. These student researchers are not motivated by an imperative to publish, nor are they seeking a key to the gates of the academy; rather, these young scholars embody a paradigmatic shift that is at the core of the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor. Their research approach is informed by the contextual understandings developed in lecture halls and reading rooms but cedes formative authority to the inhabitants of the territories of poverty.

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference. These student researchers are not motivated by an imperative to publish, nor are they seeking a key to the gates of the academy; rather, these young scholars embody a paradigmatic shift that is at the core of the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor. Their research approach is informed by the contextual understandings developed in lecture halls and reading rooms but cedes formative authority to the inhabitants of the territories of poverty.

Stephaine Ullrich, a senior pursuing degrees in Peace and Conflict Studies and Media Studies, will work along with Anh-Thi Le, Aviya McGuire, Somaya Abdelgany, and Rebecca Peters, on the development of a book to be published next semester. In addition to a deep interest in global citizenship, Ullrich and her student colleagues share a new outlook on development practice and research.

Ullrich, who has worked on a variety of initiatives in Spain, Guatemala, northern India, and Uganda, has entered academic research after a great deal of in-the-field experience. While in India, Ullrich worked for Tata, one of the largest companies in India. During her time there, she conducted research aimed to increase the role of women in the management of water wells. She then completed her GPP practice experience in Uganda, where she worked with the Uganda Village Project on its “Healthy Villages” project. Ullrich worked with community-based organizations on efforts to increase virus awareness.

Student research assistant Rebecca Peters, a senior in International Development & Economics, shares Ullrich’s community-oriented approach. “I didn’t say, ‘I’m here to help you,’ but instead said, ‘let’s have a conversation,’” explained Peters, recounting her research approach in Cochabamba, Bolivia. During the summer of 2012, Peters conducted interviews and surveys in Bolivia to document rural access to water and sanitation services. She chose to work with Agua Para el Pueblo (water for the village), largely because of the value this NGO places on community relationships and participation. This commitment to listen rather than impose is among the transformative innovations of the GPP experience.

The cautiousness displayed by Peters and Ullrich results from exposure to the multitude of failed systems that together create conditions of poverty. The fear of inadvertently reinforcing these structures through their fieldwork is itself an attribute of the new generation of poverty scholars. Yet Peters and Ullrich do not allow consciousness to become disabling.

“Not becoming paralyzed is something that the minor really helps you with,” explained Peters. She reasoned that the GPP minor’s coursework on the ethics and morality of fieldwork allowed her to gather research while challenging north-south development paradigms.

In addition to their research with Professor Roy, Peters and Ullrich co-teach a student-led deCal course on water and international human rights. In their second semester of teaching, Peters and Ullrich expose 30 students to international discourses of human rights and water and their relationship to public policy, anthropology, sociology, economics, and even philosophy. In addition to examining case studies, Ullrich and Peter’s course bring in guest lecturers, and concludes with capstone group presentations.

The new generation of poverty scholars is bound neither by disciplinary borders, linear development theories, nor dichotomous understandings of poverty. Perhaps, more than progressing from practice to theory, this young group of scholars is forcing theory and practice to develop not as a binary, but together as one.

Abby Van Muijen discusses the Visual Notetaking DeCal and the ways in which this learned skill can improve the learning experience both in and outside of the classroom.

Author:

Christina Gossmann

Abby Van Muijen graduated from UC Berkeley in 2012 with a major in urban design. Now she works at the Blum Center as a Visual Communication Specialist, developing a new learning tool for the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor and teaching a class on visual notetaking.

What is visual notetaking? Regardless of whether you’re putting a box around a word, improving your handwriting or sketching out entire pages, visual notetaking is all about breaking away from the conventional structure of notetaking that we’ve all fallen so helplessly into. We’re imagining alternatives to the spiral bound notebooks we all have–the ones filled with nothing but lines and lines of words that we will undoubtedly throw away at the end of the semester.

What is visual notetaking? Regardless of whether you’re putting a box around a word, improving your handwriting or sketching out entire pages, visual notetaking is all about breaking away from the conventional structure of notetaking that we’ve all fallen so helplessly into. We’re imagining alternatives to the spiral bound notebooks we all have–the ones filled with nothing but lines and lines of words that we will undoubtedly throw away at the end of the semester.

How did you start visual note-taking? I actually started visual notetaking while I was studying abroad. I was listening to guest lectures, working on projects, visiting sites and being given a lot of information, but the structure of the program made me feel like I didn’t need to remember everything. So I only wrote down the things I really wanted to remember. I would write words really bold or draw boxes around them and spent a lot of time doodling, drawing and listening. At the end of the trip, I had a sketchbook full of just the things I wanted to remember. But more than just having pages that sparked a lot of interest aesthetically, I felt like I was learning much more efficiently. I didn’t have to re-teach myself everything I had copied down in lecture anymore. I could look back at the visuals I had made and remember what I was thinking when I made them and studying felt more like reading a comic book than painfully trying to cram information into my brain.

What is The GPP coloring book? It is a compilation of all of my visual notes from Ananya Roy’s GPP 115 course from last fall when I took the class. This fall, students have been experimenting with it as a learning tool. Half of the book provides a visual outline of the lecture material so that students can sit in lecture and focus on understanding the main concepts, rather than worry about copying down every detail. The other half of the book consists of pages designed for students to fill in their own thoughts, questions, opinions and any other details that they feel are significant–the things they want to remember. The goal of the coloring book is not to get students to start bringing crayons to class, but rather to go beyond the black and white information they are presented with and add a bit of “color” of their own.

What is The GPP coloring book? It is a compilation of all of my visual notes from Ananya Roy’s GPP 115 course from last fall when I took the class. This fall, students have been experimenting with it as a learning tool. Half of the book provides a visual outline of the lecture material so that students can sit in lecture and focus on understanding the main concepts, rather than worry about copying down every detail. The other half of the book consists of pages designed for students to fill in their own thoughts, questions, opinions and any other details that they feel are significant–the things they want to remember. The goal of the coloring book is not to get students to start bringing crayons to class, but rather to go beyond the black and white information they are presented with and add a bit of “color” of their own.

You teach a class on visual note-taking at Berkeley. Who takes this class and how do you go about teaching? I took my first drawing class my sophomore year in college. On the first day, they told us to spend 15 minutes drawing whatever we wanted. I drew a tree that looked like a stick of cotton candy with a small, slightly ill-looking stick figure that I initially intended to be myself, but out of embarrassment, put a top hat on and labeled as Abraham Lincoln. Needless to say, it was an incredibly unimpressive effort. That was two years ago. I wasn’t magically bestowed with the ability to take notes the way I do. It was something I practiced every day, and taught myself how to do. I started Visual Notetaking 101 because I realized that this is a skill that people can learn. Visual notetaking can revolutionize your entire outlook on your education, as it did for me. Seeing your thoughts and ideas and opinions come to life, even if just on paper, is empowering. Rather than feeling sleepy and confused at the end of a lecture and having gained nothing more than a headache and a few pieces of binder paper that I won’t look at until the midterm. I now walk out of lecture feeling brilliant, creative and accomplished every day, holding on to a few pages of paper that I might cry if I lost. And that’s what I came to UC Berkeley to do, to be inspired each and every day not just by my professors, but my myself and my classmates.

How does the class work? Visual Notetaking 101 is designed so that everyone can participate. We have about 150 students from all different majors, ages, drawing abilities and walks of life. We meet every week for an hour and a half to take on a new element of visual learning beyond just visual notetaking, everything from fonts and page layouts to engaging presentation slides and résumé design. Each class starts off with a review, a quick lecture, a series of workshop activities, and for homework, we practice more. For the final review at the end of the semester students must come up with a project that is visual, academic and awesome. Last year’s projects were absolutely phenomenal–I’d encourage anyone interested to come check them out this year.

How does the class work? Visual Notetaking 101 is designed so that everyone can participate. We have about 150 students from all different majors, ages, drawing abilities and walks of life. We meet every week for an hour and a half to take on a new element of visual learning beyond just visual notetaking, everything from fonts and page layouts to engaging presentation slides and résumé design. Each class starts off with a review, a quick lecture, a series of workshop activities, and for homework, we practice more. For the final review at the end of the semester students must come up with a project that is visual, academic and awesome. Last year’s projects were absolutely phenomenal–I’d encourage anyone interested to come check them out this year.

The Final Review for Visual Notetaking 101 will take place on December 4th in the Blum Center classrooms.

How UC Berkeley professors, Ananya Roy and Tara Graham, are using social media in the classroom to help students become more engaged and foster a new academic community where all voices are heard.

Author:

Javier Kordi

Twitter has played a critical role in helping oppressed citizens challenge totalitarian regimes around the globe. Being able to transmit messages to a global audience within seconds, the site has led to a phenomenon that social scientists call “ambient awareness:” the notion that we can possess omnipresent knowledge of the whereabouts of friends, celebrities, organizations, and most recently, the course of history—all through 140-character blurbs of information known as “tweets.”

The micro-blogging service helped overthrow Mubarak in Egypt and challenge information blackouts in China, but in Ananya Roy’s Global Poverty and Practice class, it took on quite a different hue. While the sight of 700 students using their gadgets during class may resemble anarchy for some, a new sort of classroom community was being fostered through the use of Twitter.

Professor Roy described her mission as establishing “a democratic means of communication, [to] change how we learn and how we interact.” No longer restrained by the convention of hand-raising or one’s shyness, students were given the opportunity to have their ideas heard. In the realm of Twitter, students are free to exchange ideas, challenge others, and even alter the course of the lecture.

Professor Roy described her mission as establishing “a democratic means of communication, [to] change how we learn and how we interact.” No longer restrained by the convention of hand-raising or one’s shyness, students were given the opportunity to have their ideas heard. In the realm of Twitter, students are free to exchange ideas, challenge others, and even alter the course of the lecture.

As Professor Roy delivered her lecture on Jeffery Sachs and William Easterly, a live Twitter feed was projected on the screen behind her. Grouped under the hash-tag #GlobalPov, a mosaic of ideas and commentary materialized behind Professor Roy, back dropping her lecture and adding a new dimension of interaction.

Tara Graham, the architect of this project, explains how it seeks to “encourage a many-to-many lecture”, where “the feed becomes the focal point” of the classroom. Chipping away at the tradition of hierarchical education, the Twitter project restructures social relations within the classroom.

While most professors have chosen to outright ban social networking during class, the approach undertaken by Professors Roy and Graham reflects a new ideology. Tara argues that “the idea in pedagogy is figuring out how to reach the ‘millennial generation’. Instead of complaining about these tools, the faculty needs to start confronting the tools.” This is particularly relevant in the context of the Global Poverty and Practice curriculum, where students are being trained to be active members in the public debates surrounding development. Being a public medium, Twitter allows anyone to join the conversation, but also forces Berkeley students to think of themselves as public scholars— everything they post falls under the scrutiny of the global community.

This is certainly uncharted territory. In the digital age, student’s engagement with scholars shouldn’t be limited to black-and-white texts on the tables of Doe Library. While students discussed the debate between Sachs and Easterly on the #GlobalPov Twitter feed, they were a mere “@” symbol away from sending their messages directly to these scholars’ personal Twitter accounts. Professor Graham concludes: “It can do for academia what it has done for celebrity culture… how people feel like they have a direct connection with the celebrity. Academics don’t have to be so distant… there can be more of a connection.”

Ultimately, Twitter has the ability to disintegrate barriers and foster a new academic community where all voices are heard—even those thousands of miles away from Wheeler Hall.

At the Territories of Poverty Conference, Emma Shaw Crane discusses how to challenge traditional approaches to tackling poverty by leaving the academic setting and going into the field to ensure that theory “rides the bus”.

Author:

Christina Gossmann

“When people ask me what I do and I tell them that I work on poverty, I get one of two responses,” Emma Shaw Crane told a room full of attendees during her closing remarks at the Territories of Poverty conference. “One answer is ‘Oh my God, I love KIVA [a non-profit microfinance institution]! I actually have this woman that I’m lending five dollars to every month’ or I get the raised eyebrows and ‘Oh, how is that going?’”

The audience chuckled, and Shaw Crane continued to explain that these common reactions represented the often limited scope of thought about poverty scholarship.

The audience chuckled, and Shaw Crane continued to explain that these common reactions represented the often limited scope of thought about poverty scholarship.

The interdisciplinary, intergenerational two-day conference took place on the 14th and 15th of September and was hosted by the Blum Center for Developing Economies and the Department of City and Regional Planning. In two panels on Friday and one panel on Saturday morning, 12 academics from different disciplines, each with a unique set of experiences and opinions, worked on expanding the definition of poverty scholarship. The discussion was built around three major themes: new paradigms of the welfare state, the ethics of encounter and geographies of penality and risk.

Working at the intersection of these three themes, Shaw Crane was not afraid to challenge traditional poverty scholarship and the scholars who had influenced her throughout her academic and professional career. As an undergraduate at the University of California Berkeley, she was surprised to learn that “experts on poverty” had often learned about poverty in an elite environment, a trend that Shaw Crane felt necessary to change. Instead of staying in the classroom, theory should dare leave academia to enter the field; in essence, theory should “ride the bus,” Shaw Crane suggested, borrowing the metaphor from poet Ruth Forman. Shaw Crane decided to pursue the minor in Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) because it undermined the hierarchy of top-down poverty scholarship.

“The minor is a project of dislocation,” Shaw Crane said. “Because it sends undergraduates, me included, into the field to engage in the messy and contradictory and complex work of poverty alleviation and the work of building power with community organizations and government institutions.”

Shaw Crane’s own path since graduating from UC Berkeley can be seen as a testament to this interdisciplinary approach of theory and practice. After receiving the University Medal, an award given to the student with the most outstanding academic record, Shaw Crane researched the impact of the new healthcare system in the lives of families living with HIV in Bogotá, Colombia as a Fulbright fellow. She returned to the Bay Area to work in a community health clinic and organizing project in Oakland, until she joined the Blum Center as a research fellow earlier this year. Together with Professor Ananya Roy, Shaw Crane co-directed the Territories of Poverty conference, a get-together of her “intellectual dream team, an inter-generational, inter-disciplinary wish-list,” as she jokingly referred to the panelists.

According to Shaw Crane, the conference is also a project of dislocation, from studying “the bodies and places and behaviors and choices of the often pathologized poor” to examining and challenging institutions that manage and govern poverty. Poverty then, explained Shaw Crane, is no longer a problem of specific people, “for whom the rest of us can choose to engage with, with benevolence and often tremendous self-importance,” but poverty is a larger process that reflects how capitalism works, how inequality is produced, spatialized and governed and how the middle-class makes and unmakes itself.

In her closing remarks, Shaw Crane brought attention to another inspirational piece within this new paradigm of poverty scholarship that was introduced by Michael Katz, Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. Not only do the conference and GPP minor provide specific implementation strategies, but they show that the gap between theory and implementation is filled with power, “very serious and constructive and problematic and complex, but nonetheless, power,” Shaw Crane said.

“That is something I need to write on a Post-It note and carry around with me for the rest of my life!” With these words, she looked into the audience of practicing poverty scholars and poverty scholars to be. Many heads nodded in agreement and numerous hands took the note down, to make sure not to forget.

It is building awareness around the notion of power and possibility—through this conference and the minor—that enables new frontiers in poverty scholarship.

The Daily Californian, the student-run UC Berkeley paper of record, visited Prof. Ananya Roy’s “Global Poverty: Challenges and Hopes In The New Millennium” class this week to explore her use of Twitter in a large lecture hall setting. According to the article:

By projecting tweets pertaining to the class on a screen, professors are able to use teaching methods that allow large groups of students to interact with one another and the professor during class.

The tables have turned,” said Tara Graham, director of Digital Media Projects at the Blum Center and a lecturer in the campus international and area studies department. “We’re no longer in a world where ideas are conveyed one-to-many, but now we have a many-to-many mode of communication.”

…

“What this does is that there are so many kids that are speaking up, and because we run it live, they then engage in conversation with each other in a way that’s impossible in almost any classroom,” Roy said. “This is not anymore about my simply lecturing to them; I’m curating the conversation.”

To read the full article, click here.

By now, it’s common knowledge that Twitter and other forms of social media are transforming the ways in which our students engage with each other (and celebrities) outside of the classroom, but what about the ways in which these media tools can transform student participation and interaction during class? Or, inversely, the ways in which the classroom can transform the tone of discussions and sharing on social media? And, in turn, the ways in which these digital platforms can empower a generation of digital natives to speak up and weigh in on matters of public importance?

“There is nothing new about using social media in the classroom,” argues Tara Graham, a lecturer in the International and Area Studies Academic Program at the University of California, Berkeley. She has been using Twitter as a platform for dialogue and discussion in her classes on digital media and social justice for over a year. Graham’s workshop-style classes, however, are small in size, ranging from 15 to 20 students. The question follows:

Could Twitter encourage substantive discussion in large lecture hall classes with hundreds of students?

Graham teamed up with another UC Berkeley colleague, Ananya Roy, chair of the Global Poverty & Practice Minor, to put the question of scale to the test. Roy teaches a class on global poverty every fall that attracts at least 600 students. Early this semester, the two unleashed a live twitter feed into the auditorium, and the experience was wild.

Continue reading “#GlobalPOV: From Public University To Twitterverse”

On a rainy Wednesday evening, 23 UC Berkeley students from a broad range of disciplines gathered for class in a seminar room in the imposing University Hall—each taking a seat around a mysterious “Hello Kitty” stuffed doll. After a few minutes, the table was filled with seemingly unrelated products: cartoon toothpaste and toothbrush sets, a doggy-bag dispenser and a manicure set.

Author:

Author:

Luis Flores

On a rainy Wednesday evening, 23 UC Berkeley students from a broad range of disciplines gathered for class in a seminar room in the imposing University Hall—each taking a seat around a mysterious “Hello Kitty” stuffed doll. After a few minutes, the table was filled with seemingly unrelated products: cartoon toothpaste and toothbrush sets, a doggy-bag dispenser and a manicure set.

The lesson of the week was the potential of “bundling” products and services in public health. Creatively integrated with a colorful first-aid kit, the “Hello Kitty” emergency stuffed doll illustrated a way to incentivize the adoption of responsible health practices using cultural tastes. It is no surprise that a course focused on developing innovative solutions is taught creatively as well.

Often described as one of the most innovative courses on campus, Designing Innovative Public Health Solutions, a course sponsored by Blum Center, gives students an invaluable opportunity to engage with real clients in developing cutting edge solutions to real public health problems. “There are a lot of opportunities to do things much better,” explained course instructor Jaspal Sandhu, who holds degrees from MIT and UC Berkeley.

Often described as one of the most innovative courses on campus, Designing Innovative Public Health Solutions, a course sponsored by Blum Center, gives students an invaluable opportunity to engage with real clients in developing cutting edge solutions to real public health problems. “There are a lot of opportunities to do things much better,” explained course instructor Jaspal Sandhu, who holds degrees from MIT and UC Berkeley.

He said the course was designed to address a “need for applied skills” in approaches to public health. The course imparts the innovative approach of understanding problems, not from a theoretical perspective, but from the perspective of practitioners and recipients of public health. “We often design a good fix to the wrong problem,” lamented Jaspal.

Course co-instructor Nap Hosang, lecturer of Community Health and Human Development, advises students on their projects.

Andrea Spillmann, who recently received her MPH, was among the first group of students to enroll in Jaspal’s course. “Most of our other courses teach you what’s been done and why and how,” Andrea remarked, “either teaching you how to replicate that or why you should not replicate that.” While Andrea finds those skill sets helpful, the course on Designing Innovative Public Health Solutions helped her critically approach the root of problems and to reframe both problems and solutions in unconventional ways. Andrea’s project reflects this critical approach.

Working with Tal Amiel, an MPP candidate, Andrea began working with Tekla Labs to develop cheaply and readily available blueprints for lab equipment in Nicaragua. However, after traveling to Nicaragua for a pilot program, Andrea and Tal noticed problems overlooked by their clients. “We noticed a drawer full of pipettes, unused because no one knew how to calibrate them,” recounted Andrea. It became apparent that health labs in Nicaragua did not need more equipment but needed to maintain and fix the equipment they already had.

Working with Tal Amiel, an MPP candidate, Andrea began working with Tekla Labs to develop cheaply and readily available blueprints for lab equipment in Nicaragua. However, after traveling to Nicaragua for a pilot program, Andrea and Tal noticed problems overlooked by their clients. “We noticed a drawer full of pipettes, unused because no one knew how to calibrate them,” recounted Andrea. It became apparent that health labs in Nicaragua did not need more equipment but needed to maintain and fix the equipment they already had.

Andrea and Tal then redirected their efforts at a more pressing problem, proposing the development of videos, plans, and a hotline to connect labs in Nicaragua with experts elsewhere who could give them advice on how to maintain equipment.

Photo Credit: Jaspal Sandhu

This semester in Jaspal’s class, students are working in groups on seven different projects, ranging from the development of a prototype investment module for drinking water franchises in rural Mexico to an initiative to increase MediCal enrollment in California’s Santa Clara Valley.

Taking about an hour of the three-hour class, guest lectures who are innovators in different industries introduce students to creative practitioners in different fields. Guests have included Chris McCarthy, a Kaiser Permanente innovation specialist who is behind the popular KP MedRite sash—which reduces medical errors in hospitals by creating “no-interruption” wear to minimize distractions in the administrating of medication.

Another inspiring lecture by a New York Times author showed the success for channeling youth rebellion away from smoking. By showing how tobacco companies work to manipulate the youth, a pioneering campaign to promote youth rebellion against tobacco companies became highly effective in reducing teenage smoking.

If the past is any indicator, students will continue to be drawn to the course, which “turns traditional analysis completely inside out,” as Ruco Van Der Merwe, a current student in the course, explained. Perhaps just as important, the course will help develop a new community of professional practitioners in public health who are unafraid to critically engage with traditional paradigms and who are poised to innovate for the public good.

Nearly two centuries after Thomas Edison proclaimed that “We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles,” 1.6 billion people continue to suffer from light poverty—more than the entire population of the world at the time of Edison’s breakthrough. Having to rely primarily on kerosene—and an odd mix of other sources, including candles, fish oil, yak butter, twigs, diesel fuel, and even footwear— people are constantly exposed to dangerous fumes and fire hazards which contribute to a panoply of health problems and climate change.

Author:

Author:

Javier Kordi

When set on fire, a sandal made of discarded tire rubber emits eight hours of low grade, dirty light. Although unconventional, in Southern Kenya—where a lack of grid electricity and shortages of kerosene, batteries, and wood cause people to burn whatever is at hand— such extreme measures are not uncommon. One interviewee reported burning about six sandals every year.

Nearly two centuries after Thomas Edison proclaimed that “We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles,” 1.6 billion people continue to suffer from light poverty—more than the entire population of the world at the time of Edison’s breakthrough. Having to rely primarily on kerosene—and an odd mix of other sources, including candles, fish oil, yak butter, twigs, diesel fuel, and even footwear— people are constantly exposed to dangerous fumes and fire hazards which contribute to a panoply of health problems and climate change.

In 1995, after witnessing the darkness of rural India, scientist Evan Mills set out to create the LUMINA Project—an initiative based at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory committed to combating the light poverty of the developing world. After a decade of laying the groundwork on a shoestring, an investment by the Rosenfeld Fund for Sustainable Development at the Blum Center in 2007 helped the organization to pick up momentum. Today, LBNL and Humboldt State University scientists and engineers are deploying systems for evaluating the quality of systems based on white light-emitting diodes (WLEDs) and conducting important market research and field tests—in collaboration with product manufacturers— striving to deliver the promise of sustainability, durability, and affordability. Many students at both universities have been involved.

LEDs are by no means a new technology, but before LUMINA, no systems were in place to consistently test the quality of small off-grid lighting systems. When some lighting manufacturers began introducing low-quality products into the market, LUMINA was ready. With lifespans as low as a few weeks, the only notable outcome produced by low-quality devices was disappointment. Product testing work done previously by LUMINA quickly revealed the consequences of bad design and the potential for better outcomes. ‘Lighting Africa’, an initiative of the World Bank and of other partners inspired by LUMINA, created a system based on LUMINA’s work to test and certify new products. Inspired by a report commissioned from LUMINA in 2011, the U.N.’s Clean Development Mechanism passed a new methodology for combating light poverty while enabling carbon emissions reductions achieved by new technologies to be valued and traded through the Clean Development Mechanism. Titled “AMS-III-AR”, this international framework sets industry standards for off-grid lighting products receiving carbon-trading credits. These regulations are harmonized with the Lighting Africa standards. Additional “points” are received by products that perform even better. A series of market trials conducted in Africa by LUMINA have proved promising—people are eager to purchase solar-powered LEDs and showed high levels of satisfaction with their quality-assured new lights (the latest trials in Kenya are documented in LUMINA’s Project Technical Report #6). Following the World Bank’s lead, U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu launched an initiative on off-grid lighting at the Copenhagen climate conference, and is now supporting LUMINA’s work.

With this new technology and framework, the prospect for growth is immense. In 2010, Evan and colleagues conducted a field trial using LEDs in poultry production (where kerosene is the norm). Lighting a large chicken coup (3000 chickens!) with LEDs instead of kerosene cut operating costs dramatically and created a safer environment for farmers and chickens. This year, Berkeley students Tim Gengnagel and Phillipp Wolburg are in Tanzania working with fishermen on Lake Victoria. Every night, about 22,000 fishermen take to the lake with kerosene pressure lamps to attract their catch. In recent years, yields have been plummeting due to climate change and pollution. These night-fishermen spend up to a dollar a day per lantern on kerosene—a huge amount of their income. LEDs could change the economic equation dramatically, and fishermen have indeed been happy with the LED prototypes brought to them by LUMINA.

With this new technology and framework, the prospect for growth is immense. In 2010, Evan and colleagues conducted a field trial using LEDs in poultry production (where kerosene is the norm). Lighting a large chicken coup (3000 chickens!) with LEDs instead of kerosene cut operating costs dramatically and created a safer environment for farmers and chickens. This year, Berkeley students Tim Gengnagel and Phillipp Wolburg are in Tanzania working with fishermen on Lake Victoria. Every night, about 22,000 fishermen take to the lake with kerosene pressure lamps to attract their catch. In recent years, yields have been plummeting due to climate change and pollution. These night-fishermen spend up to a dollar a day per lantern on kerosene—a huge amount of their income. LEDs could change the economic equation dramatically, and fishermen have indeed been happy with the LED prototypes brought to them by LUMINA.

Nearly two decades in the making, LUMINA has broken new ground in the fight against light poverty. With continued support, the organization and its partners may one day bring light to all. For more information, such as updates, project reports, and photographs, visit the project’s website at: http://light.lbl.gov/field.html or Evan’s blog at http://offgridlighting.posterous.com/.

UC Berkeley is traveling back in time. The campus is on track to reduce its carbon footprint to 1990 levels in two years, with the long-term goal of achieving carbon neutrality. The drive to accomplish this began in 2005 when a group of graduates, undergraduates and faculty members drafted a letter to the administration seeking to place a cap on campus carbon emissions. The administration replied with a challenge: to put together a practical, measurable feasibility plan.

UC Berkeley is traveling back in time. The campus is on track to reduce its carbon footprint to 1990 levels in two years, with the long-term goal of achieving carbon neutrality. The drive to accomplish this began in 2005 when a group of graduates, undergraduates and faculty members drafted a letter to the administration seeking to place a cap on campus carbon emissions. The administration replied with a challenge: to put together a practical, measurable feasibility plan.

The result was CalCAP, UC Berkeley’s Climate Action Partnership, a student-led initiative that took up the daunting task of calculating all of the University’s emissions and drafting recommendations to the administration.

“No university at the time had tried to inventory what it’s carbon emission was at that point,” explained Scott Zimmerman, a graduate of Boalt Law School who helped develop CalCAP during his time as a graduate student. “It just made sense that we would try to tap into what is going on in the labs and use the campus as a testing bed for those ideas.”

After taking first prize at the first Big Ideas@Berkeley contest, CalCAP gathered a group of eight students to comprehensively measure the campus’ carbon footprint. Considering everything from faculty and staff commutes, fugitive emissions of refrigeration, and even student’s air travel, the resulting feasibility study of 2007 convinced the administration to accept CalCAP’s proposed targets.

Former CalCAP project manager, Fahmida Ahmed believes the group’s success is due to the genuine passion of the students involved. For students, it was very personal.

“It was important for it to be home-grown,” noted Fahmida, who now works as the Associate Director of Stanford’s Office of Sustainability, “We wanted our institution as a whole to look within and understand where we are and where we want to go from there.”

Seeded from a modest award from Big Ideas, CalCAP has grown immensely. The organization has gone on to inspire other UC campuses to adopt similar emission targets. Yet even with the added responsibilities, students have continued to play an active role in the initiative. Every year, graduate students enrolled in the Sustainability in Action: CalCAP course conduct extensive greenhouse gas emission inventories in order to evaluate the campus’ progress toward its sustainability goals. The latest study found that the UC Berkeley campus is currently exceeding the 2014 target by 42,000 metric tons of carbon emissions.

In addition to policy suggestions, like the switch from coal to natural gas power, CalCAP is actively engaged in developing sustainable habits in the everyday lives of students. On their website, an interactive feature allows students to calculate the carbon impact of their air travel. Moreover, the just-released MyEnergy at Berkeley dashboard, a collaboration between numerous campus organizations, allows students to track energy consumption in 57 buildings on campus day by day, constantly reminding students of the environmental impact.

Environmental initiatives often struggle to garner support for goals that are marginal and difficult to see. But CalCAP’s interdisciplinary approach that strives to consider all stakeholders has ensured widespread support of its carefully chosen reduction targets. While the research of accomplished scientists on campus provides the resources for environmental progress, CalCAP shows that it often takes the drive and passion of students to push for measurable reform.

The importance of anthropology in poverty alleviation and development work was showcased at a March 8 panel discussion hosted by the Blum Center for Developing Economies, where speakers highlighted how anthropology can help us understand economics, policy and the alarming rates of poverty that persist in the world.

Author:

Brittany Schell

The importance of anthropology in poverty alleviation and development work was showcased at a March 8 panel discussion hosted by the Blum Center for Developing Economies, where speakers highlighted how anthropology can help us understand economics, policy and the alarming rates of poverty that persist in the world.

The discussion, “Anthropological Insights on Poverty in Developing Economies,” was moderated by Richard C. Blum, founder of the Blum Center, and featured four female panelists in honor of International Women’s Day.

Tett, who has a Ph.D. in anthropology, talked about the role of anthropological analysis in economic discussion and policy creation. Her recent book, Fool’s Gold: How Unrestrained Greed Corrupted a Dream, Shattered Global Markets and Unleashed a Catastrophe, focuses on the connection between social behavior and economics.“If you want to understand the world, simply plugging numbers into a spreadsheet isn’t enough,” said panelist Gillian Tett, U.S. managing editor of The Financial Times of London.

“A silver lining to the cloud of the economic crisis is that it has indeed forced a new level of interdisciplinary discussion,” Tett said. “Interdisciplinary work is key for innovation and creativity in human endeavor.”

Laura Tyson, an economics professor at UC Berkeley and Chair of the Blum Center Board of Trustees, also talked about the power of interdisciplinary approaches in searching for innovative solutions to global poverty.

“People are now coming together, bringing serious psychological and anthropological lenses on what happened,” Tyson said, referring to the economic crisis.

There is a growing interest among her business students, Tyson said, around the idea of creating for-profit business ventures that will bring value to communities—more than just the products or services provided. Her students want to create business models that “understand the actual needs of the population we are trying to serve,” she said. Aihwa Ong, a UC Berkeley anthropology professor, said anthropologists are observing and trying to understand how things work in the constantly changing conditions of globalization, and so are hesitant to make big claims about solutions to poverty.

“We have to think of culture not as fixed blueprints of society,” Ong said. “Culture is not written in stone, but rather is a dynamic system of beliefs and practices.”

All four panelists agreed that, as teachers, they have an opportunity to show students an anthropological means of looking at problems like poverty, hunger, clean water, and other issues faced by people in developing nations, to help build sustainable solutions that work for the local community.

Clare Talwalker, vice chair of the Global Poverty and Practice minor at UC Berkeley, said she teaches her students that poverty alleviation is about listening and learning, which is where the field of anthropology becomes so important.

“The work of alleviating poverty and inequality begins by focusing on actual relationships that are formed on the ground,” she said.

Talwalker emphasized that teachers have the responsibility and opportunity to guide future employees of NGOs and multinationals. “Students can be powerful agents of change,” she said. “Our students are the aid workers of the future.”

Eight students from the Blum Center for Developing Economies at UC Berkeley will participate in the Clinton Global Initiative University (CGI-U) hosted at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. starting on March 30th. All are part of the Blum Center’s “Global Poverty and Practice Minor,” the largest undergraduate minor on the Berkeley campus.

Students are selected to attend CGI-U based upon the quality of their “Commitment to Action” – a specific plan of action that addresses a pressing challenge — on their campus, in their local community, or across the world. Three of the Blum Center students have also been honored by an invitation to present their action plans to the audience.

Presenting their work will be:

Lauren Herman, a recent Cal graduate who majored in Peace and Conflict Studies, made a commitment to create informational material for Kenyan borrowers who are vulnerable to predatory lending. An attendee at last year’s CGI U, she will return this year to share the progress she’s made since last year’s commitment. Her work aims at helping Kenyan borrowers, who are often unaware of the loan conditions and their rights as consumers. To address this problem, Lauren has been working on a consumer education manual. This new resource will assist clients in making informed decisions about their participation in microfinance. It will be distributed in collaboration with consumer advocacy groups and microcredit borrowers in Nairobi.

Komal Ahmad, a fourth year student majoring in Interdisciplinary Studies and Jacquelyn Hoffman, a fourth year student majoring in Gender and Women’s studies, made a commitment to addressing inequitable distribution and injustice in the food system. Their organization, Bare Abundance (BA), collects excess food from on-campus dining halls and restaurants to redistribute to those who don’t have healthy food. They have developed an after-school program operating in Oakland and staffed by current UC Berkeley student volunteers. School children learn about the importance of a healthy lifestyle through BA’s experiential method, where participants prepare and consume the healthy food collected through the BA network. Komal and Jacquelyn aim to expand their afterschool program and hope to create food redistribution initiatives on other college campuses.

Attending for the first time will be:

Stephanie Ullrich, a fourth year student with a double major in Peace and Conflict Studies and Media Studies & Rebecca Peters, a third year student majoring in Society and Environment , made a commitment to a 3-part water initiative. They will create a Water Sustainability, Science, and Development minor at UC Berkeley to educate students on global hydro-politics, health and sanitation; they will expand membership in the Berkeley Water Group, an interdisciplinary student group that addresses problems related to water, sanitation, and hygiene; and they will create an academic water research journal and social marketing campaign to improve outreach.

Joanna Chen, a third year student majoring in Urban Studies, made a commitment to work with local NGOs to preserve the ecology of rural China. She will offer workshops on the environmental rights of villagers in rural areas. By engaging marginalized groups in education about their rights to a safe environment, Joanna hopes to spur local activism and encourage policy reforms that will protect the vulnerable environments of China.

Thuy Ngan Pham, a third year student majoring in Molecular Toxicology, made a commitment to develop a network to raise awareness and gather funding for student-run service organizations. SAnoda, a citizen organization, will develop an online database to connect students and faculty to the needs of the UC Berkeley service community. By linking student initiatives to their much-needed funding, SAnoda aims to increase the efficacy and frequency of social action.