By Alisha Dalvi and Sam Goldman

Navigating around town, tailoring our workouts to our level of physical fitness, knowing when our packages will arrive: The boom in data collection and analysis has been a boon to our daily lives — and a new paradigm for businesses, organizations, and governments to optimize efficiency and improve services. It feels ubiquitous. Who hasn’t taken advantage of the digital revolution?

It turns out, many communities haven’t been able to. From marginalized neighborhoods nearby to many areas around the globe, the tools that increasingly govern and improve our lives are not available or not tailored to serving everyone, be it personal wellbeing, environmental health, or economic security.

But under a new NSF-funded research program housed at the Blum Center, the Digital Transformation of Development (DToD) Traineeship, students are using their research skills to apply digital tools, such as machine learning and AI, to the issues and challenges of poverty alleviation, disaster relief, and more — in pursuit of digital and technological justice, equity, and empowerment.

“There’s a lot of recognition of the potential of rapidly emerging technologies like AI, new analytics, scalable cloud computing, and novel data sources,” says Matt Podolsky, DToD program coordinator. “But these advancements have not been particularly targeted to under-resourced communities and issues that pertain to them. We aim to address that shortfall.”

After an initial planning year, the five-year program kicked off Fall 2022 with its first cohort of nine master’s and 16 PhD students. Though their formal traineeships center around three DToD-themed courses that are taken over two or more semesters, the program aims to keep them involved for the entire duration of their graduate studies. A handful of fellows receive one-year awards covering tuition and fees, plus a stipend; the fellowship also offers the unique opportunity to apply for travel grants for self-arranged internships, where they conduct fieldwork and applied research with and within low-resourced communities. For PhD students, the program additionally allows them to work toward the designated emphasis in Development Engineering, an official minor for PhDs. The interdisciplinary skills developed in DToD include everything from technical writing skills to ethical data collection, all with the goal of producing fair and inclusive analysis to benefit underserved communities.

One of the key courses students take in the Development Engineering ecosystem, “Design, Evaluate, and Scale Development Technologies,” provides a hands-on opportunity to develop a tangible solution — say, a simple-to-use, easy-to-carry solar-powered water pump — to real-world problems — say, climate-impacted farmlands. The focus is always on incorporating the context and needs of people and their communities.

“It encourages students to develop a solution that involves the end users in the design process and could be scaled beyond just a small research prototype,” says Podolsky.

Another class, “DToD Research & Practice,” is a seminar featuring guest speakers including thought leaders and researchers from UC Berkeley’s faculty and experts in industry applying AI and data technologies for social impact, who work on everything from how to incorporate AI in development to finding early signs of eye disease using machine learning. This class also allows students to present their own work to peers, providing feedback to each other while learning about interesting research across campus. That model fosters collaboration, support, and skills in communicating research to those outside one’s discipline.

—

Rajiv Shah, former administrator of USAID and former Blum Center trustee, approached Prof. Shankar Sastry during multiple board-of-trustee meetings about building on the Center’s mission.

“The brand of the Blum Center is really technology and mechanisms, incentive designs, and so on to lift people out of poverty,” says Sastry, the Center’s former faculty director, the College of Engineering’s former dean, and DToD’s principal investigator. “And Raj said, ‘Why don’t you take it to the extreme? And why don’t you see how you can combine these latest greatest technologies?’”

Thanks to Development Engineering pioneer Prof. Alice Agogino, the Blum Center already had a track record of success with National Science Foundation Research Traineeship (NRT) programs. Meanwhile, Dr. Yael Perez, director of the Center’s Development Engineering programs and the coordinator for the InFEWS NRT, felt it would be a boon for students with digitally minded social-impact projects to receive the same kind of holistic support that InFEWS students had for their own social impact work. She hoped to see more social impact–minded students come out of programs like those of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. And Shah’s idea came back to Sastry.

“It became rapidly clear that technologies in AI and machine learning, as well as Internet of Things and cloud computing, all of that was booming,” he says. But what he found missing was “how you would bundle them into services that could then be offered for people to better themselves, and at scale.”

Around 2019 and 2020, “by the time we were putting this [program] together, most corporate boardrooms were talking about digital transformation. And they didn’t exactly know what they were talking about,” Sastry adds. “But we taught that by digital transformation, we really meant: How do you take these advances in AI, machine learning, IoT, cloud and edge computing to provide services — be they in healthcare, in energy, in distributed energy management — to be able to really enable economic development.”

“We could give our students an appreciation not only for these algorithms,” he says, “but also what happens when you use them.”

—

The first cohort’s fellows come from disciplines and departments across campus, from various branches of engineering to city and regional planning to the School of Information. Over 60 percent of the first cohort are women and nearly half are underrepresented minorities.

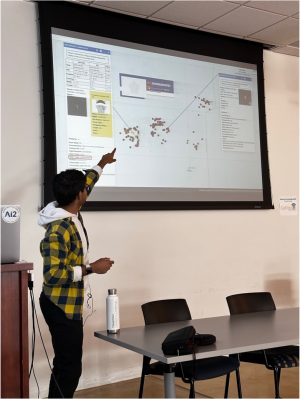

Among this first class is Ritwik Gupta, a PhD student at Berkeley’s AI Research Lab, who focuses on computer vision for humanitarian assistance and disaster response, along with public policy for the effective and safe usage of such technology. Working with a diverse set of partners such as CAL FIRE, the Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Unit, and the United Nations, his research on tasks such as assessing damage to buildings from space and detecting illegal fishing vessels in all weather conditions has been deployed worldwide.

The work of classmate Evan Patrick leverages geospatial science and ethnography to evaluate forest restoration efforts in Guatemala and explore the ongoing impacts of the El Niño Southern Oscillation on landscapes and livelihoods in the country. The Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM) PhD student worked with two MDevEng capstone groups in the Potts Lab to model the carbon benefits of plantation expansion in Guatemala and to use social media audience estimates to investigate ENSO-driven internal migration in Central America.

Sarah Hartman, in her fifth year of an ESPM PhD program, first got involved with the Blum Center through its first NRT on innovations in food, energy, and water systems. She wanted to continue what had been an “absolutely wonderful experience,” and DToD just happened to be relevant to her work using technology, engineering, and science to improve water and agricultural conditions in low-resource settings.

“The way the program’s designed is really nice,” she says, “because it gives you exposure to people who might be outside of your discipline but are using methods that might be of use to your particular application.” For instance, in one DToD class, a visiting professor discussed how she translated the skills and technology involved in using AI to build others’ personal wealth into using AI to detect early health concerns in low-resource settings.

The programs’ benefits, however, extend beyond official class content.

“I really appreciate the balance they strike between professional opportunities and community-building opportunities,” Hartman says. “And sometimes it’s the small things.”

Like coffee and cookie breaks. Students like Hartman find inspiration and collaboration during opportunities to socialize during class. “There’s a lot of value in the informal conversations that we have around the structured lecture content,” she says.

Take, for instance, Gupta’s work using machine learning and satellite imagery to understand the toll Russia’s war in Ukraine is having in cities. His methods, Hartman found, could add a new layer to her work understanding how the war is impacting Ukrainian agricultural resilience, such as better, faster insight into the status of key agricultural infrastructure like grain silos and ports. This cross pollination improves her ability to conduct real-time analysis in a continuously evolving situation.

—

Going forward, Podolsky plans to implement more workshops on topics from data visualization to effective communication skills, such as op-ed writing. “We really just want to add to the research training aspect beyond just coursework,” he says.

But in the big picture, Sastry says, the DToD program is about more than just the implementation of digital development solutions in accordance with the needs of people in under-resourced settings. It’s also about what comes before that process even starts.

“I think it’s great to do interventions, it’s great to think about clean water, it’s great to think about energy,” he says. “But what’s really emerging from this series is students getting a sense of empowerment to go and change the world. And that quite often transcends specific solutions. I think we’re giving them that, and we’re giving them some optimism.”

“Because at the end of the day, the technology is great, but it’s the starting point,” he adds. “It’s not the endpoint; the services are the middle point; and then the empowerment for people is really the endpoint. So it starts with empowering our students to empower the people to help themselves.”